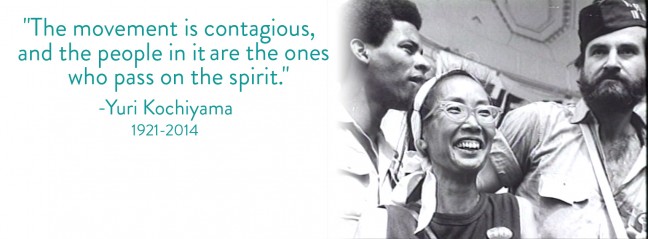

The late civil rights activist, Japanese American Yuri Kochiyama, is the subject of Rea Tajiri’s Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice (1993), a CAAM-distributed documentary.

Hear from Yuri Kochiyama herself – here are a few of her quotes from the documentary. In addition, we have an essay by NY-based musician, writer and educator Taiyo Na.

On people of color uniting:

“My priority would be to fight against polarization. Because this whole society is so polarized. I think there are so many issues that all people of color should come together on, and there are forces in this country who want this polarziation to take place.”

“Unless we know ourselves and our history, and other people and their history, there is really no way that we can really have positive kind of interaction where there is real understanding.”

“Political philosophy is not just something you obtain, it’s something that you develop through your lifetime. And of course, as different events happen to you and different people you meet and writings that you read, your philsophy is going to change.”

“Remembering what happened, not to my happened to my father, but to Japanese as a whole, I see similiar things that happened to other ethnics. Years later, I would see that these kind of things happened to others all along, all the time, especially to blacks.”

More about the film:

Yuri Kochiyama’s story begins with her internment as a young woman during World War II and her gradual political awakening. A follower and friend of Malcolm X and a supporter of Black Liberation, Kochiyama was at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem when Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965. She has been involved with worldwide nuclear disarmament, the Japanese American Redress and Reparations Movement and the International Political Prisoner Rights Movement. Through the astonishing breadth of her activities, Kochiyama has united people who otherwise might not have met. A typical yet significant example was when she initiated a meeting between Malcolm X and the Hiroshima Nagasaki Peace Study Mission from Japan. This event kindled her close friendship with Malcolm X that would endure until his death.

Through interviews, writings, music and archival footage, this film captures the extraordinary vitality and compassion of Yuri Kochiyama as a Harlem-based activist, wife, mother of six children, educator and humanitarian. Her accomplishments and continuing involvement offer a unique view of past struggles in human rights and an inspiring glimpse at possibilities for the future.

+ + +

Yuri, Tupac, and a Harlem House

By Taiyo Na

Originally posted at Hyphen

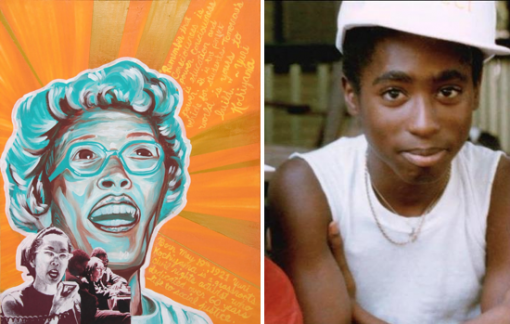

One of my favorite stories about Yuri is also about Tupac. In an event curated by the late Fred Ho in celebration of Diane Fujino’s 2005 book release of the biography Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama, Laura Whitehorn spoke of the activist harbor that was the Kochiyama house. Dubbed “Grand Central Station” or the “Revolutionary Salon,” this Harlem apartment and Kochiyama family residence was a hub for activists, artists, students and other community members for much of the last four decades of the 20th century. Whitehorn recalled a then 9-year-old Tupac Shakur speaking eloquently and passionately about the need to free political prisoners at a meeting in Yuri’s house. This 9-year-old Tupac was, of course, not just talking about abstract historical figures, but members of his own family — his stepfather Mutulu Shakur, his godfather Geronimo Pratt, Sundiata Acoli, Sekou Odinga, and others.

That image of Pac as a child speaking about the struggle to free his politically imprisoned family members at Yuri’s house was something very moving to me. It spoke of the insurmountable courage of Pac’s childhood, and it spoke of the prodigious compassion of Yuri and the Kochiyamas to continually share their space. It also embodied the interconnectedness of our struggles. Because if a Japanese American woman such as Yuri and Malcolm X were a hard pairing for people to imagine, then undoubtedly in public imagination Yuri and THUG LIFE are too; and what people don’t understand about Yuri reveals exactly how much we don’t understand about social movements.

Yuri and Pac’s families were profound friends, comrades in intense post-Malcolm struggles for Black and Third World Liberation. Trace the lineages, and one can see how the legacies of both families and their communities catalyzed movements that transformed the nation and world twice over. Whitehorn’s snapshot of Yuri and Pac was like listening to “Free the Land” by Chris Iijima, Nobuko Miyamoto, and Charlie Chin on the A Grain of Sand album. Pac’s stepfather Mutulu Shakur is literally singing there with them on that record, and they are collectively singing the ethos of Malcolm’s call for the self-determination of all oppressed people.

Whitehorn’s brief story here also illustrated how these are struggles political and personal. Pac often talked about how Movement radicalism left women like his own mother raising families on their own while the men in the family were incarcerated, assassinated or absent. Pac’s politicization as a child was parallel to the immense trauma and loss he must have felt as a child of war under siege by the FBI’s COINTELPRO. This is not unlike Yuri’s own experiences during World War II, how just prior to her family’s forced removal to a concentration camp, her own father, a leader in the Japanese American community in San Pedro, CA, was illegally detained, interrogated and denied medical care by the FBI for six weeks and died the day after he was released.

Yuri and Pac both turned their pain into power.

Through the usage of informants and anonymous letters, COINTELPRO FBI agents created friction in the Movement through fiction. Yuri, however, never wavered. She was “the person,” as Angela Davis described in tribute, “who can really change the world.” “This is the person we all need to emulate. We need to emulate her because she knows that the most important work is in the details, in the small things, in the letters, in the words exchanged between us, in the smiles, in the love.” Yuri combated polarization with inclusiveness. She was the safe space. Yuri’s ability to sustain positive relationships amongst Movement activists across generations must be seen as resistance against oppression in the highest of forms. Indeed, she was her own rose that grew from concrete — or concentration camp. And best of all, she planted and helped blossom many, many more.

As we continue to memorialize Yuri, it is vital to not see her as a flash in the pan, but water in a neverending river for justice. For the next generations especially, to connect the dots between Kendrick Lamar, Pac, Malcolm and Yuri. She herself would have made the transnational political connections occurring in today’s world from Gaza to Ferguson, generationally between Emmett Till to Mike Brown, Vincent Chin to Renisha McBride; Mumia to Snowden; White supremacy and imperialism to neoliberalism.

The spirit of Yuri is in our interconnectedness. Yuri Kochiyama, eternally, presente.

UPCOMING MEMORIALS FOR YURI KOCHIYAMA:

LOS ANGELES

August 31, 2014 (Sunday)

2:00 – 4:30 pm

Aratani/ Japan America Theatre

244 South San Pedro Street (bet. 2nd & 3rd Sts.)

Los Angeles, CA 90012

NEW YORK

September 27, 2014 (Saturday)

5:00 – 7:30 pm

First Corinthian Baptist Church

1912 Adam C. Powell Boulevard

New York, NY 10026

***

Taiyo Na is musician, writer, and educator from New York City. When he was an awkward 19-year-old, Yuri generously remarked with a smile how his poetry was “firebrand.”