Ten years ago, Michael Siv was one of the subjects in Spencer Nakasako’s documentary Refugee, which centers around Siv and his quest to reunite with his father and brother in Cambodia. Siv, with one documentary already under his belt (Who I Became, 2003), is behind the camera on his sophomore project, Wounds We Carry.

The film follows a group of Cambodian Americans as they return to Cambodia to observe the Khmer Rouge Tribunals. The group consists of genocide survivors, including Cambodian-born advocate and professor at California State University, Long Beach Professor Leakhena Nou, and Siv, who documents the trip. Along the way, they encounter Hong Siu Pheng, the son of convicted war criminal Kang Kek Iew (a.k.a. Duch), who oversaw the notorious Tuol Sleng (S-21) prison, where as many as 20,000 people were killed. In a twist of fate, Pheng unexpectedly decides to join the group on their search for justice.

Wounds We Carry, a CAAM production, is the recent recipient of the prestigious MacArthur Foundation’s Documentary Film Grant. Ashlyn Perri sat down with Siv to discuss his personal history, his career, and updates on the project.

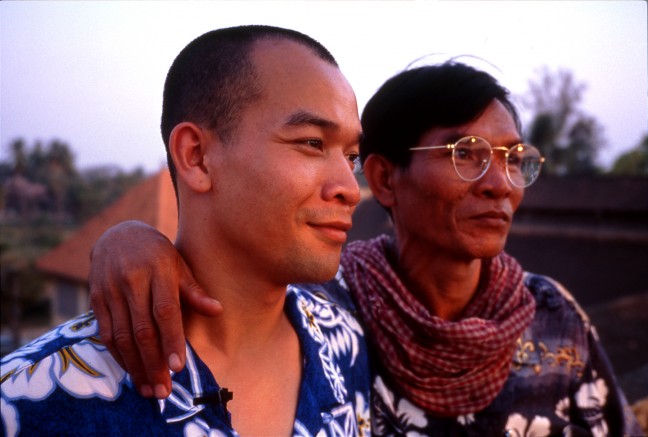

Michael Siv filming in Cambodia (left) with Hong Siu Pheng (foreground). Photo courtesy of Michael Siv.

How does it feel to get the MacArthur Grant?

Of course I’m happy. This is sort of like one of those things where we didn’t really expect it. When the news came, it was kind of one of those things where you’re like ‘Ok now I can make the film.’ With the funds I think we’re able to reflect a little bit. Let’s think about how to make the film as best as it can be.

What is your background and your relation to the Cambodian Genocide?

Long story short, my Mom and I were in (a) camp separated. Men and women couldn’t be together, so me and my mom were in one camp, and my dad and my brother were in another camp. When the Vietnamese invaded, everybody had a chance to escape. So my mom and I, somehow, were fortunate enough to make it to the Thai refugee camp. My dad stayed behind (in Cambodia). That’s pretty much my connection with the genocide. When we were in the camps I was 2-3 years old. So, the good thing is, I don’t remember any of it. The bad thing is, I went through it.

I think there’s a certain block. I don’t want to remember it. I guess if there was therapy I might’ve, but I wouldn’t want to go through it. I don’t want to remember what was happening. I’m fortunate enough that, by the time we immigrated to America, I was already 5, maybe 7, years old. I’m pretty sure I remember some stuff, but it doesn’t affect me growing up in America. These other guys who are older than me didn’t graduate high school. Or they were too old to go through the assimilation of being in America. For me, I think it was hard—growing up in the TL (Tenderloin district of San Francisco), a lot of the families were separated.

How did you get involved in documentary filmmaking?

When I was fourteen, I tried making a short. There’s this youth center, called the Vietnamese Youth Development Center. As part of a peer resource group, at the center, there was an arts program. So a guy named Spencer Nakasako was running the video workshop. For ten years, I hated working with him ’cause I was thirteen, fourteen, and in high school all I wanted to do was play basketball and work.

Ten years after, I think I was at (San Francisco) State and he—after his film with a.k.a. Don Bonus and Kelly Loves Tony—wanted to think outside of the box. So he was like, “Hey Michael, you think some of these guys might want to take a workshop in the summer?” And I was like, “As long as it’s not me.” (Laughing) I was the one who connected him with some of the other guys that I was playing (and) coaching basketball for. They started taking some of his workshops.

So his theory has always been, give this kid a camera, let them tell them a story. There are no guidelines. Just take the camera home, shoot whatever you wanna shoot. But then you have to just look at the camera and you have to talk about something you’re interested in. So all these bad-asses that were on my team, none of them would wanna do it. So during that summer, I had to show these guys. It wasn’t hard for me. So I took the camera home, and for whatever reason, I talked about my dad and my mom being separated.

Michael Siv in the documentary, Refugee.

Spencer never knew that. He asked me to do it (Refugee). Despite my friction with him, I figured that one, it’s as a free trip, I’d get to go meet my Dad (laughing). Two, I’d get to go visit Cambodia and all that kind of stuff. Three, I was probably a little bit older, and basketball wasn’t the priority.

So somehow it ended up me staying on. I didn’t go to film school or whatever, but I think that based on what I’ve learned, I don’t think I really need to.

How do you see your film fitting at all into this post-Khmer Rouge film narrative?

I’m just tired of the Khmer Rouge. I’m tired of their story. Why, when we talk about Cambodia or we talk about this community, (is it) always what the Khmer Rouge have done. They dictate our lives. Is that always going to be a part of who we are when people talk about Cambodia? How (are we) going to help the survivors find closure to this history? And I think that’s one question that I always had. My mom’s obviously affected by it and my dad, obviously, affected by it. But nobody talks about their story.

Who do you want to reach through this film? Is it second generation Cambodians, like yourself, or everyone else?

Deep down inside I still think, for me, it’s more for the Cambodian audience. I think it’s important, not only for the first generation, for the second generation for the Cambodian population as a whole that there’s this unresolved situation with this war.

We have seven characters that represent so many elements of this Cambodian community. I think if a Cambodian person, whether it be first generation, second generation, or third generation, they will relate to it. They will have some sort of character that they can connect to.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.