In Bruce Lee’s posthumous book, The Tao of Jeet Kune Do, he encourages the reader to maintain a flexible outlook in both martial arts and life itself: “If nothing else within you stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves. Moving, be like water. Still, be like a mirror. Respond like an echo.”

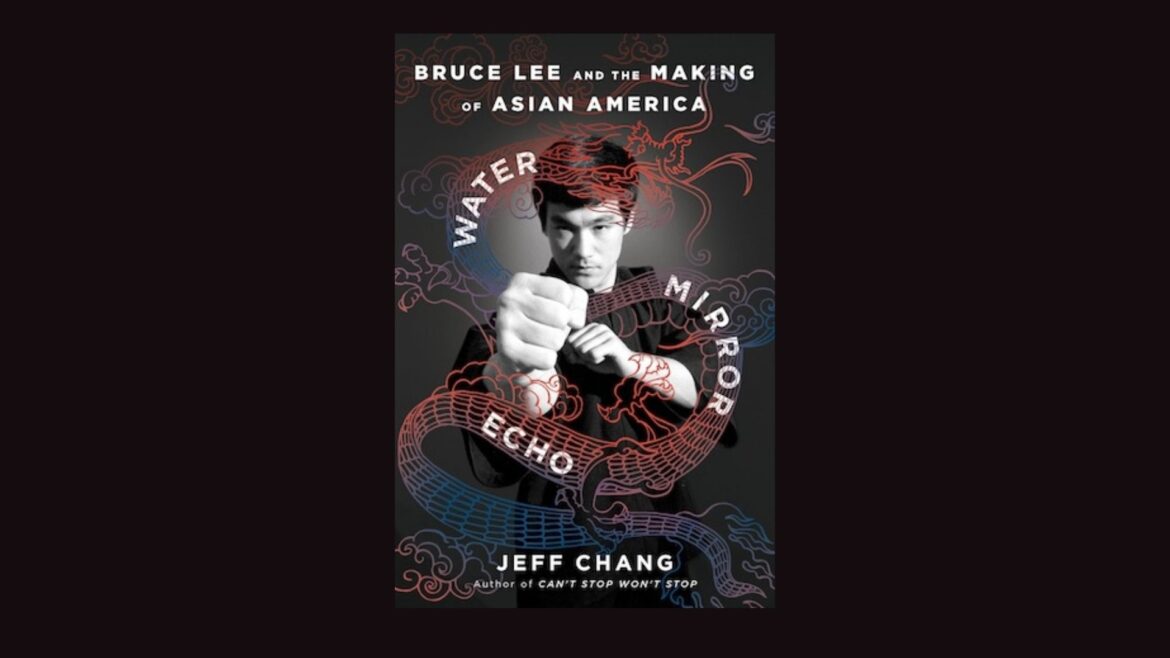

This quote is the inspiration for the title of Jeff Chang’s new biography, Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America. One of many books written about Lee in more than half a century since his untimely death, this one aims to reconstruct the legend that has since eclipsed the martial arts movie star, getting to the core of who he was as a person and how his life and work shaped what Asian America is today.

Although Chang signed on to do the book quite a while back, the majority of the writing took place within the last few years. During this time, the anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID pandemic became a driving force for the book’s direction.

“We were all going through this, I don’t know, collective identity crisis,” he explained over Zoom. “Do we belong? Are people seeing us? Are they recognizing our suffering and pain? How do we overcome this together? And so, as we’re having all these existential questions collectively, the image of Bruce reappears on social media feeds, on the walls of Chinatown and Asian American communities all across the country, and I’m just like, ‘Oh man, there’s something happening here.’”

The more the author learned about Lee and saw parallels to both his own life and that of his family, he became drawn to this bigger connection that had yet to be explored: how the icon continues to be a major influence on the evolving Asian American culture.

“It’s not just about Bruce’s story standing in for us,” Chang said. “It’s also about Bruce being this representative of who we are and it’s about how the things, ideas that folks are developing in Asian America at the same time are filtering into what Bruce is becoming as well.

“It’s not this process of assimilation. It’s this process of actually learning what it means to be a racialized minority that makes him American,” he later added.

Chang cannot recall a single moment where he first became aware of Lee. While he was too young to see his films when they initially came out, growing up in Hawaii, the icon was otherwise everywhere: on TV, in locally made zines, and in magazines imported from Hong Kong or California.

Aside from similar family histories, the parallels between the author and his subject became even more aligned, with Lee mixing different styles of martial arts, from conversations he had with martial artists from Hawaii.

“In Hawaii, they were already mixing up all of the different schools in the 20’s and the 30’s,” Chang elaborated, “and so that’s what influenced Bruce a lot, was all of these folks who had actually been engaged in testing out all of these different types of styles with each other to see what would work, because they’d been doing that for two generations in Hawaii before.”

This fact is one of many revealed in Water Mirror Echo. Aside from collecting research from periodicals, magazines, zines, and so on, Chang also conducted research from rare and private documents belonging to Lee, as well as from interviews with his confidants. In the process of research, Chang formed a friendship with Shannon Lee, Lee’s daughter and CEO of the Bruce Lee Family Companies, who gave access to those sources.

“Shannon was basically like, ‘You know what? I’m going to give you access to my father’s papers and his things, his ephemera and all that stuff, and you can make of it what you are. I’m not going to look over your shoulder. I’m not going to edit you, I’m not going to try to tell you what you should write, but I am trusting you with this,’ which was pretty heavy,” he recalled. “It was a pretty heavy kuleana. It was a heavy responsibility, and so I went into it gingerly, but as I was going back and forth between these things, everything started to become a lot clearer.”

Chang also credited filmmaker and CAAM Mentor Bao Nguyen, who in 2020, released his exploration of Lee’s life with the documentary Be Water; the two would share a lot of ideas as both projects were in production. “I was really influenced by him, particularly just scenes in his movie and the way that he approached Bruce, and certainly the people that he interviewed and all that kind of stuff really influenced me a lot too,” he said.

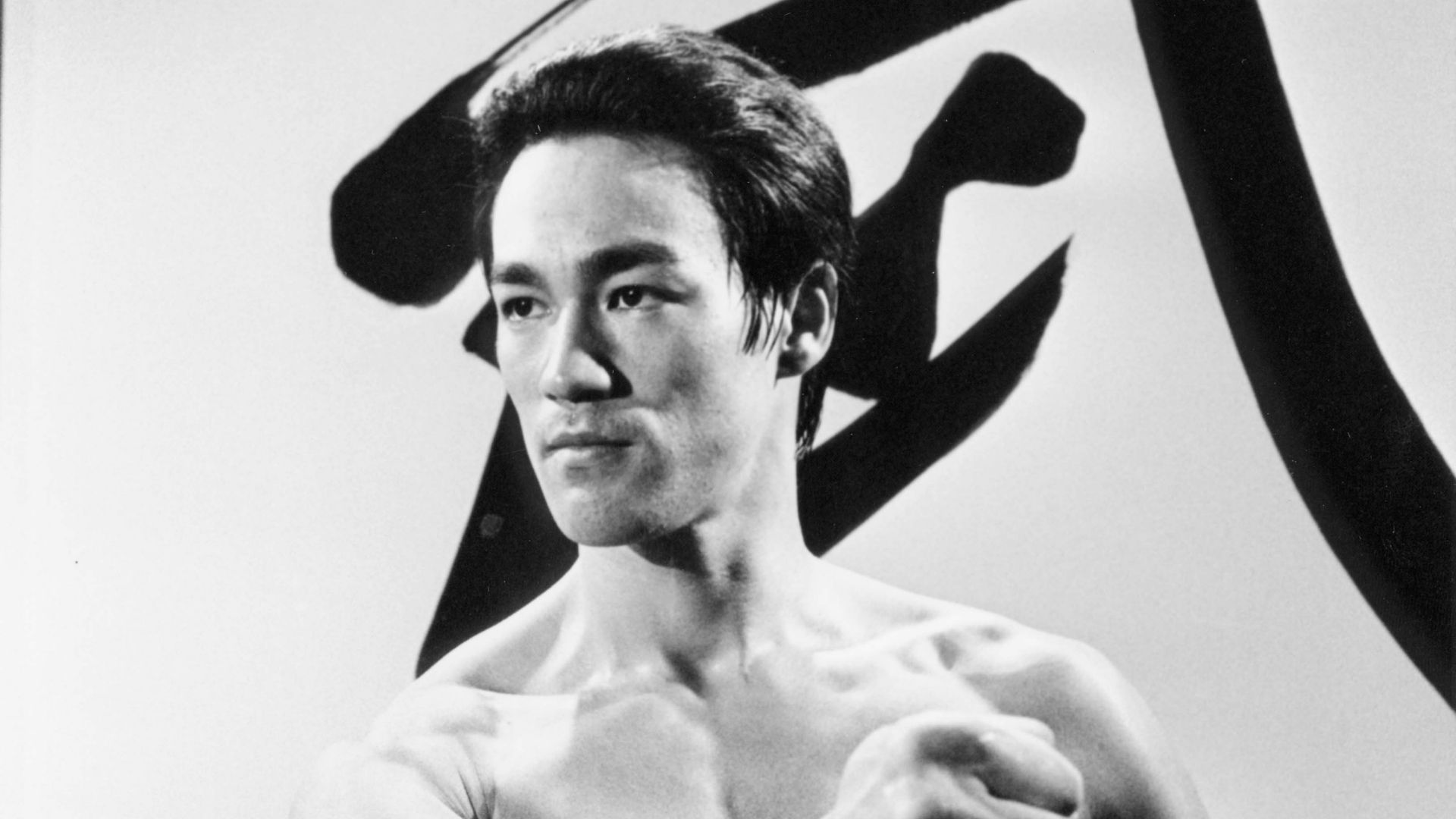

In all the new information Chang was learning about Lee, the most surprising one was just how vulnerable the action star was. For all his onscreen depictions of characters saving the day, fans might assume he was equally confident in his real life. Chang points out that family and friends revealed that Lee sometimes had doubts about himself.

An example is the toll from all the arguments he got into when making Enter the Dragon, such as insisting the title be changed from the original Han’s Island. “It’s like classic Hollywood take on the Oriental, that the Oriental can only be a villain and that it’s probably easier for somebody who is not Asian, who is white to pick up on an inanimate rock than to imagine the Asian as a hero,” Chang said.

“So, Bruce intimately felt these things and he felt he needed to fight those things,” he added, “and it’s a testament to what he had to overcome to look at that particular period really closely, and it’s also revealing of just how vulnerable he really was.”

Water Mirror Echo follows a string of biographies centered on foundational Asian and Asian American figures in Hollywood, such as Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong by Katie Salisbury and Love, Queenie: Merle Oberon, Hollywood’s First South Asian Star by Mayukh Sen. It also comes just a few short months before, what would have been, Lee’s 85th birthday.

Chang sees the timing of these releases as a reconsideration of their lives, and that the pandemic got a lot more people rethinking these representations, in what he considers to be a really interesting time for Asian America in general.

“We came out of the pandemic. There’s also this explosion of representations of us in the media,” he explained. “Maybe Everything Everywhere All at Once is like the perfect encapsulation of that where you literally have this movie where it’s like, we’re going to show you all the ways that we can be. We’ll show you all the ways even just one character can be in all these multiverses, and I just thought that was brilliant. All of a sudden, the game had changed. There was this massive expansion, and it wasn’t the big boom. It was maybe the third big boom since Bruce.

“With this explosion, to think about the rethinking Anna May and Merle and Bruce in that context is I think something that’s historic, and it hopefully helps to contribute to the discussions that you all are having as makers and creators about how to take this idea of Asian America and then again remold it and reshape it and remake it in your generation’s image,” he added.

Looking ahead to what will come of Lee’s legacy, Chang finds the mystery not in who he was, but why he continues to evolve in each generation’s mind. However, he feels that the one conclusion that was settled in 2020 is that he is a symbol of strength, pride, unity, and solidarity – leaving it up to the new generation to learn what they will from the details.

“That idea of Bruce as a projection, we’ve in each generation projected onto him our hopes and dreams, sometimes our fears too, and so that changes and it’ll be really interesting to see how he continues to grow,” Chang noted. “It’s a little bit like the question people always ask me, ‘What’s the future of hip-hop?’ I don’t know, shit. Ask a 12-year-old, you know what I mean?”