In 1936, actress Merle Oberon was nominated for her role as Kitty Vane in The Dark Angel, at the Eighth Annual Academy Awards. Eighty-seven years before Michelle Yeoh became the first Asian actress to win Best Actress in a Leading Role, Oberon was the first actress of Asian descent to be nominated for that honor — and only actress of South Asian descent to be nominated to this day.

However, the groundbreaking nature of her achievements would not be apparent until a few years after her death, when the 1983 biography, Princess Merle: The Romantic Life of Merle Oberon, revealed, what is perhaps, the greatest performance of her career. While the world knew her to be a white woman born and raised in Tasmania, Australia, she was actually Queenie Thompson – an Anglo-Indian woman from present-day Kolkata, India.

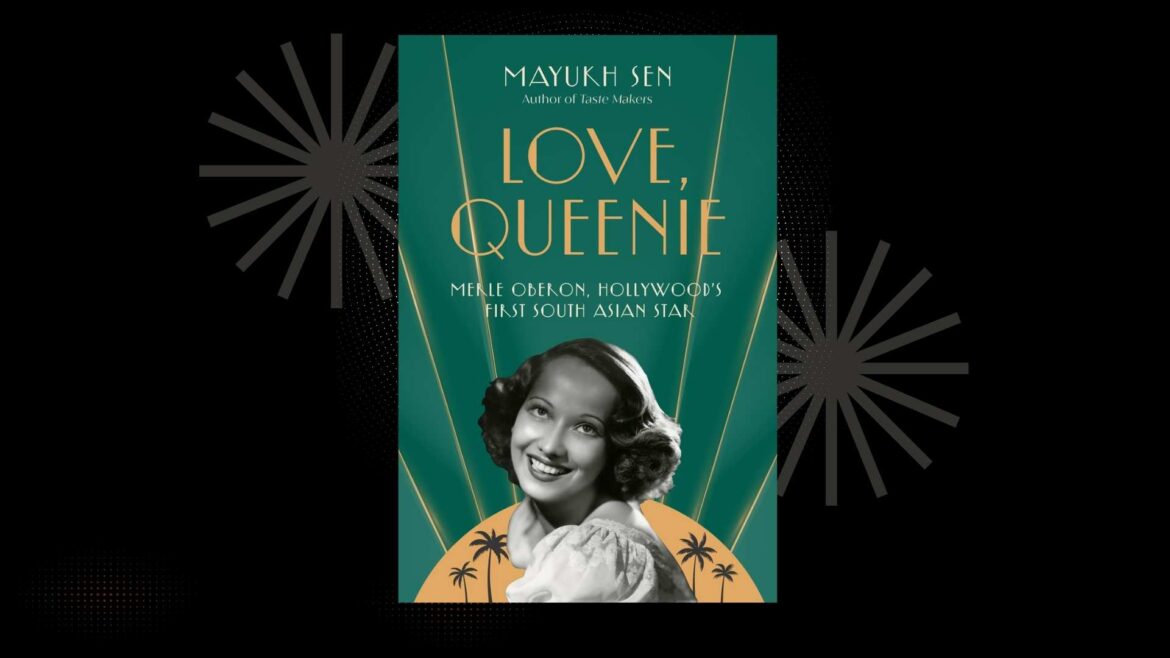

Mayukh Sen, author of the new biography Love, Queenie: Merle Oberon, Hollywood’s First South Asian Star, explores the struggles the actress endured in both her life and her career, as both South Asian and mixed race. Her story is one he’s been wanting to explore since the summer before his senior year of high school. A self-proclaimed Oscar obsessive and coming from a family of cinephiles, he wanted to freshen up on the history of Best Leading Actress, when Oberon came onto his radar.

“I was just stunned when I read her story because she grew up in the same part of India that my dad is from – Kolkata or Calcutta – and I already felt a connection in that sense,” he explained in an interview over Zoom. “But there were so few South Asian faces who were populating Hollywood screens even at that time in 2009. We [were] on the heels of the massive success of Slumdog Millionaire, and many of us believed that Freida Pinto, for example, was going to be tomorrow’s big star.”

In learning about her history and what she endured in order to maintain a career in Hollywood, Sen related to her struggle to hide her true identity, as he had yet to come out as gay at the time. He wanted to understand why she made the choice to pass as white, which is why he promised himself then to write a book about her.

One of his goals with his biography was to reconstruct and double check the information published in Princess Merle. Co-authored by Charles Higham and Roy Moseley, as Sen explained, the former was known amongst older Hollywood circles to “sometimes play fast and loose with facts, and maybe fabricate some details about his biographical subjects’ lives for the sake of some narrative verve and color.”

“Back then, the nature of publishing was such that there aren’t really end notes or the kind of proper sourcing that so many authors like myself are beholden to,” he added, noting that his book contains almost as many pages of endnotes as the text itself. “But I don’t want to be too hard on Charles Higham, because I think that what we do as authors is hard. He was really one of the first to put on the record that she was indeed born in India rather than in Tasmania. ”

Sen researched diligently about the history of Oberon. Finding her interviews and other press materials unreliable due to her lying about herself, he dug deeper; eventually contacting her surviving family members, who were able to put a lot about her life into perspective.

They cleared up a lot of misleading information, like the belief that she was also of Māori descent. Another major reveal came in the form of the identity of her mother, who was originally believed to be a woman named Charlotte from Sri Lanka. In actuality, Charlotte was Oberon’s biological grandmother, whereas the woman she believed to be her half-sister, Constance, was her mother, having given birth at only 14 years old.

But what Sen found to be most surprising is that Oberon rarely, if ever, felt safe. She arrived in the United States in a time when the 1917 Immigration Act was in place, that barred people from what was considered India at the time from immigrating. In 1923, a Supreme Court ruling also barred immigrants from obtaining citizenship based on race.

“I think that there is this misperception of Merle, that because she passed as white that she just had the most charmed life possible, and she was just using that privilege to get ahead,” he said. “But what I really wanted to do was to push my readers to think about those systemic barriers that she was up against.”

Even when both those laws became obsolete with the passage of the Luce-Celler Act in 1946, Oberon still faced a lot of risk, due to animosity towards South Asians. As a result, she never applied for American citizenship, despite expressing a desire to. “She built her name on this performance of denial orchestrated by her publicists early in her career, even as American attitudes towards South Asia—its people, its culture—changed during her lifetime,” Sen added later over email.

Love, Queenie clarifies and corrects a lot of information that was otherwise well known about Oberon. But to Sen’s surprise, he encountered a lot of skepticism from old Hollywood fans. Even though the revelations of Oberon’s race came directly from her family, some challenge it because it doesn’t align with their preconceived notions. That has been disheartening for Sen to encounter, such as when on Mother’s Day, he posted a photo of Oberon’s mother on Instagram, only to be met with remarks about her complexion and whether or not she and Oberon were really related.

But for all the deniers, there has also been praise and feelings of validation from readers who, like Oberon, are mixed race. Sen recalled how much they relate to her experiences and how they too find themselves stuck in a similar bind – a bind that was on full display to him, when former Vice President Kamala Harris ran for president last year, and was met with invalidating remarks from politicians and commentators about her identity as a Black and South Asian woman.

“It breaks my heart that Merle’s story still has so much to teach us about the way the United States treats mixed race individuals,” he commented. “Hers isn’t just the story of the country we once were, but the one we still are.”

Love, Queenie was released this past March, in a stream of books about foundational Asian and Asian American figures in Hollywood; following last year’s Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong by Katie Salisbury, and ahead of Jeff Chang’s upcoming Water Mirror Echo: Bruce Lee and the Making of Asian America. Despite being on a similar historical playing field as her counterparts, Sen argues that Oberon is not held to the same regards, often being omitted or vilified from narratives on Asian representation onscreen, due to her being mixed race and white-passing.

Sen’s research did not turn up any evidence that suggests Oberon wished to be white, and he hopes that the book will encourage more empathy towards her situation and more awareness of the larger system she was navigating.

“What Merle was trying to prove throughout her career is that she can do this too, despite people not believing that she can, despite the system around her designed to constrain her, ” he said. “I do think that is her legacy, and however long it takes for people to accept that, I’m willing to wait and listen and fight on her behalf.”

Aside from coming to her legacy’s defense going forward, Sen is already working on ways her story can exist, beyond just Love, Queenie. While he didn’t specify how, his hope is that people will respect the truth of her story, instead of denying her origins. Even now, he still remains in contact with the family members he had interviewed for the book, and said how they always wonder what became of this blood relative of theirs who had such a tough time, that she wound up leaving India.

“They’re real people, and no one can take Merle away from her family,” he emphasized. “I feel protective of her. By that same token, as I think about other ways in which her story can exist beyond just the page, I want to make sure that whomever I might collaborate with will respect the truth of that story and just see its emotional and spiritual truth.”

1 Comment