The past three years have been an amazing time for Asian American cinema – the number of films being made has grown enormously (as has the quality) and a growing number of these films are finding their ways into theatres (via some forward-thinking distributors, or through self-release strategies), and then onto DVD.

Long the biggest challenge for Asian American cinema has been one of access – finding a way for the films that are being made (and we know they are being made, and are good!) to reach the eyeballs of people (who we know will want to see them, as evidenced by the long lines at any of the fine Asian American film festivals out there). There are many barriers around ideas of access, but most lie at the highest levels, the companies that are reluctant to invest dollars in releasing a film in a market that they don’t know much about (ie: Asian America).

The bottleneck of distribution is definitely there, but an equally big obstacle is marketing and outreach – actually getting people into the theatres. Having a film in a theater doesn’t necessarily mean people will be sitting there watching it. Hollywood films have marketing budgets that would eclipse the entire production budget of most indies by many times – getting the word out is an expensive thing to do. And most Asian American films are not flush with cash reserves.

One tool and resource that Asian American filmmakers have used as a work-around however, is the community – something that they know they can rely on (most of the time, if they play it right), and which a marketer can’t bottle up or buy. Toward this end, the current rise of Asian American films being released has been followed by a parallel growth in grassroots, community-focused marketing. Asian American filmmakers have been working to find the magic balance of asking for support from the community, without going too far and creating the turn-off of obligation or guilt. All Asian American films released today, regardless of whether they have a distributor or are self-released, employ an aggressive grassroots strategy. In a way, it has become the de facto marketing approach to reach Asian American audiences, a no-frills, low-budget strategy that can be more effective than billboards or tv commercials. In a world where big budget companies refuse to invest dollars into figuring out how to market to Asian Americans, the solution is sitting there right in front of us.

Via emails from film directors asking for support, campus visits, connections with community-based organizations, opening night parties, entire screenings bought out by employee groups, street teams, major on-line/social networking pushes and appearances by cast and crew, this labor-intensive approach, while not perfect, has evolved into a useful tool. Without it Asian American cinema would not be where it is today.

So, as you think about how you heard about the releases of SAVING FACE, FINISHING THE GAME, AMERICAN FUSION, JOURNEY FROM THE FALL, THE MOTEL and many others, and compare that against how you knew that DARJEELING LIMITED and BOURNE ULTIMATUM were in theaters, here are a few key moments in recent Asian American film history that have helped to define this.

• 2000: For the 20th Anniversary of CAAM (formerly NAATA), a national convening was held in San Francisco, gathering those in the Asian American media community to discuss the state of the field. One of the outcomes of this meeting was the creation of the “APA First Weekend Club”, an email newsletter, which would alert folks to when Asian American films were opening in theatres. The goal of the newsletter was, and continues to be, to mobilize audiences to watch films on their first weekend of release, to generate box office numbers high enough to ensure a second weekend, and then a third and so on. The idea of a big first weekend, and the role of galvanizing community to do this, is not a new one however – the African American community has long used these strategies to show off their box office strength, to great success. The Asian American community has adopted this model, and it too, has been successful, and evolved into many other, more complex strategies. (You can sign up for the APA First Weekend Club by sending an email to: APAFirstWeekend [at] aol [dot] com)

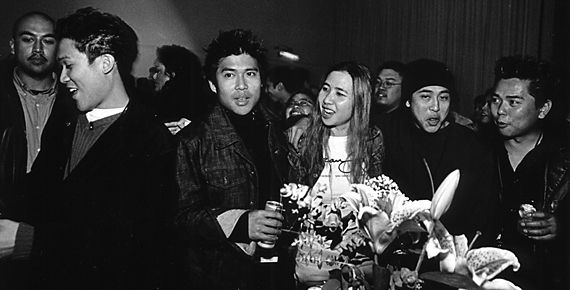

• 2001: THE DEBUT

Gene Cajayon’s modest Filipino American indie, coming-of-age feature surprised many when, using an almost exclusively grassroots, self-distribution strategy, it grossed over $1 million in the box office. Opening first in one city, San Francisco, THE DEBUT used the Closing Night of the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival as a kick off (opening the day after). Cajayon and producer John Castro spent several weeks in the Bay Area before the opening doing an immense amount of meetings and presentations to the area’s large Filipino population, the target audience for the film. Massive email lists were created, street teams roamed Daly City and other locales with postcards and t-shirts and the film’s stars were present and available to meet audiences. Amidst calls to rally around the historic moment of a Filipino American film being released in the US, and a genuine interest in individuals wanting to be a part of something, something special did happen, and the rest is history. Cajayon went on to replicate this model city by city, and by focusing almost entirely on the Filipino American community, he eventually created one of the biggest success stories of the year.

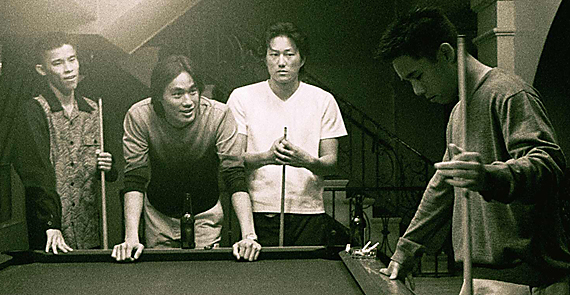

• 2002: BETTER LUCK TOMORROW

With appetites whetted from THE DEBUT’s success, Asian American audiences were ready for another film to build on and galvanize around. This film would be Justin Lin’s BETTER LUCK TOMORROW. Riding an incredible buzz from its Sundance debut, and acquisition by MTV Films, BLT took THE DEBUT’s strategy one step further. Buoyed by mainstream and critical success, Lin and his crew built a massive pan-Asian campaign around not only the film, but an idea of “cool” defined by the film’s envelope-pushing, controversial content. The result was a desire amongst young Asian Americans to see the film not only for its own merits, but to be part of a movement which could possibly define who they were, and what they stood for. The need to belong, and be a part of something were incredible motivating factors, and BLT utilized this sentiment to not only generate great ticket sale numbers (over $3.5 million box office, over $15 million in dvd sales), but also create an awareness among more Asian Americans of community and the importance of voting with one’s wallet at the box office to support Asian American cinema.

The paths created by THE DEBUT and BETTER LUCK TOMORROW would be used by many other films which would follow. Mobilizing the student population, personal appeals to audiences by filmmakers and utilizing the growing worlds of Asian American media (from Giant Robot to Hyphen to AngryAsianMan.com), would all allow filmmakers to reach audiences for a fraction of the cost of a traditional marketing campaign. (This is not to say that they would replace the impact of things such as print advertising however.) The growth of this strategy has also created many questions about its longevity, which are still to be answered, including the significant one of, after all of the “firsts” are done (first Filipino film to be released, first film to win such and such award at Cannes, etc.) how else can filmmakers convey the importance of their films?

• 2007: FINISHING THE GAME

The release of Justin Lin’s independent follow-up to BLT, FINISHING THE GAME, would give him an opportunity to revisit the strategy he helped forge, and see what its legacy and longevity is. Employing an even more extensive grass roots campaign, built around personal appearances by the film’s now well-known cast, Lin and company spent several weeks in September and October promoting the film, as well as traveling to many Asian American film festivals since the film’s premiere at Sundance in January of this year. In many ways their efforts were more intensive than what Lin had done for the marketing of his studio film FAST AND THE FURIOUS 3: TOKYO DRIFT, asking cast and crew for their personal time to travel and promote the film, and moving city to city, mobilizing their base audience.

In the greater Bay Area alone, the group visited campuses from Stanford to UC Davis, San Francisco State University to UC Berkeley, and held events with community organizations ranging from the Chinese Historical Society to the Center For Asian American Media and Hyphen Magazine. This massive campaign had the effect of not only generating great word of mouth, that magical, elusive marketing gold, but also making up for the limited resources the film’s distributor, IFC Films had to invest in traditional marketing such as TV spots and print ads. Currently in theatres, it is still to be seen how these efforts will pay off, though first weekend figures for the film have been very healthy in each of the cities the film has opened in.

Thus concludes a brief look at the wonderful world of Asian American grassroots outreach, a bit of context into how and why Asian Americans market their films in the ways that they do. Looking ahead, the cumulative effect of all of these efforts could potentially result in concrete steps forward in terms of how companies and distributors approach the release of Asian American films.

As more are released, and marketing efforts tracked, there is an increasing amount of demographic data and audience-going trends collected that are forming a more solid, demonstrateable understanding of the Asian American market, and how traditional marketing methods done in tandem with grassroots efforts can result in something even more effective (ie: make more money!).

-Chi-hui