CAAM’s Development & Partnerships Manager, Jonathan Hsieh sat down with Mahnoor Euceph, Director of Eid Mubarak, the 2024 PBS Short Film Festival Jury Prize Winner, to chat about her filmmaking journey, creative inspirations, experience working with CAAM, and upcoming projects.

This conversation is part of the quarterly CAAM in Focus newsletter series specially written for CAAM’s closest supporters. Thank you for being a part of the CAAM community and helping uplift Asian American stories!

Watch Eid Mubarak, along with CAAM’s other Asian American selection for the PBS Short Film Festival, Take Me Home, at the PBS website, PBS app, or on YouTube here.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Jonathan: First off, congratulations to Eid Mubarak on winning the PBS Short Film Festival Jury Award! One of many awards the film has won since embarking on the festival circuit. How has it been to witness the evolution of the film from its inception in grad school to now being seen at festivals around the world?

Mahnoor: I think I knew from the moment I wrote it, as an exercise in grad school, when I saw the reception the class had to it that there was an immediate spark. Just the idea of the film, and how universal and strange it was! There was something very human in it that I think all of us are confronting in different ways. This is why I always wanted to make it as my thesis film and my first film. For it to be my calling card.

Of course, the pandemic happened during my degree, so I wasn’t able to do that. I ended up picking it back up after graduating, and I think that worked out for the best. It was such a surreal process. I have never believed in a higher power more than when I was making this film, because it was one thing to write the film. It was another thing to get these opportunities to make it happen, and then to be there shooting it [in Pakistan]. With all these strange serendipitous coincidences out of my control and things working out in a way that you could have never imagined, I just had this visceral feeling when I was shooting it that I was on a chess board and someone else was controlling me for a higher purpose.

Which is silly to say, because if there is a God, why would they care about short films? But I do think that creativity comes from a spirituality, and there’s a magic to it. Of course, then, we edited it, we made it, and we had this whole festival journey, as you said.

I still feel I haven’t gotten over the positive response to the film. And I I still don’t understand sometimes what people see in it, and how they respond to it. But I think it’s become an experience of me getting to know other people better through the film and learning about them and learning about what they see in it. It’s been a whole journey for me.

Jonathan: That’s really awesome. Are there any takes or interpretations you’ve heard from audiences that surprised you?

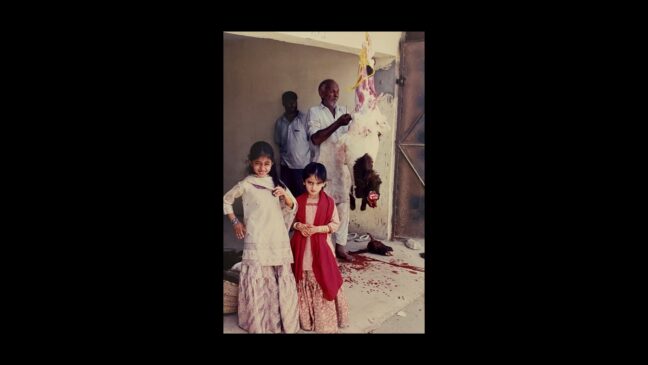

Mahnoor: Yeah, I think there’s a couple of things. For one, I made this as something for the community, from the community. I’ve always been this type of person ever since immigrating at a young age in elementary school to take the time to find teachable moments. I’m going to tell you about my culture. I felt a deep desire for my American friends to understand and to see this and be educated about a holiday that is nowhere in our curriculums, that you might just ignore or hear a random headline about. But I never intended to make this as a children’s film – I always felt it was a film for adults about a child. So it was really interesting for me to see how the children’s festivals really took it on and engaged with it and celebrated it and supported it.

My favorite part of the whole festival journey was to see all these little girls coming up to me, often sisters together, and they would tell me what they thought about the film, and how much they related to it. Girls of all different cultures. Some would tell me, “Even though your film was subtitled, it was really fun for me to watch, and I understood it”, or, “The mom was my mom” or “The sister was my sister, and I felt so bad,” and this and that.

The other thing was seeing how my own community responded to it. I always felt the difference in the energy of the crowd when it was everybody from my own community versus people for whom it’s a foreign experience. For example, the laughs! When they understand every tiny reference, and they’ve never seen that represented before on screen. That was a satisfying experience as well, to do something for my community like that.

Jonathan: Speaking to what you shared about girls coming up to you and sharing what resonated with them, were there any characters that resonated with you the most?

Mahnoor: Well, Iman is based on myself as a little girl. I think that I very much felt the way that Iman felt in the film: how when you’re young and adults treat you like you’re not really human yet, and you’re too young to understand anything. I felt really misunderstood as a kid, and I always felt really deeply as well. I was very sensitive – I still am.

What’s that song – Stuck in the Middle with You? Where the lyrics are like, “Clowns to the left of me, jokers to the right.” I felt like I was in this circus with all these adults, or older kids, who were acting like everything was completely normal and fine during this holiday. And they’re not having any of the pain I was feeling. I was constantly lost in my own thoughts and battling these conflicting emotions within myself, as a kid who really loved meat. “What’s going on? How do I feel about this?”

So I tried to show this internal journey through Iman. As a kid, you learn by watching and by observing. You’re just sucking in all the information you’re getting, and then you internalize the lessons that society is giving to you and adopt them into your value system or you don’t.

Jonathan: Another thing about the film too was just how vibrant, colorful, and playful it was. Could you share about what drives your creative process?

Mahnoor: I’ve been an “artsy” person my whole life. I was the person who would take every art class in school, and I was inspired by design and all types of art forms from a young age. I went to UCLA for undergrad and my major was Design | Media Arts, and I minored in Film, TV, and Digital Media, and also later went on to study the art market at Sotheby’s in London. So I was always trying to find connections between design, fine art, media art, and film.

Film is so influenced by technology. It’s as much a science as an art form. I felt very blessed and lucky to be interacting with technology in this really interesting way at UCLA, so I always wanted to combine all of my own influences.

I thought there was a way to combine these mediums, but also my Eastern and Western perspectives. Obviously, no society exists in a vacuum. We even have records of the ancient Mesopotamians trading with ancient Egypt and the ancient Indus River valley. We’ve all been interacting with each other forever and influencing each other.

People often say that they see a lot of Wes Anderson in my work. Well, Wes Anderson was also referencing all these great South Asian filmmakers. Everyone was referencing everyone and inspired by everyone.

Something that’s really important to me, especially as an emerging filmmaker, is to find my own visual language, and I think this was very much an experiment in how I can represent the things I love in South Asian art and imagery, that I’ve grown up with as a Pakistani, and combine that with the Western education that I have, and all of the references and everything that I love in in Western filmmaking, as well.

For example, no one does typography the way Wes Anderson does. He really has that attention to details and I love engaging with his aesthetic. But I also grew up on Mughal miniatures, which are 2D miniature paintings. They always have people in profiles with very flat colors. So depth is a different concept. If they’re showing two or three stories, they’ll be stacked on top of each other in a foreshortened type of way. It was a primary form of painting in the Mughal empire.

I always thought that was such an interesting and weird way of looking at the world and representing space, so different from the European aesthetic post-Renaissance, which was based on hyper realism.

I grew up on those images, and when I saw the opening of Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch, when they’re in this flattened plane moving up, I was taken back to the Mughal miniatures I had grown up with.

It was a process of going back and forth, back and forth. “Oh, I’m inspired by this Western thing. I’m inspired by this Eastern thing. How can I combine them?” My main goal was to show the Pakistan of my memories. I grew up in Pakistan, and I have never ever seen Pakistan represented in a fun or happy way. It’s not all terrorism and Osama Bin Laden and Slumdog Millionaire. People are happy there too. There’s all these colors. Like you’ll even see hyper masculine men wearing the most colorful, bedazzled, jeweled clothes.

Jonathan: Thank you for that answer! I feel like I was in a film class. When I was watching the film, I was actually reminded of Wes Anderson, but my next thought was that it was interesting that my first instinct was to go to that, so it’s enlightening to hear about global miniatures and the ways in which art and creativity build off different cultural expressions

Taking a bit of a turn, you referenced earlier about having the opportunity to share about Pakistani culture via your own visual language. Part of why I love working at CAAM is being able to see so many different stories and approaches and ways of expressions. We always say it: there really are so many multitudes to the Asian American diaspora. How did you learn about CAAM and how did CAAM become involved with Eid Mubarak?

Mahnoor: I’ve grown up in LA my whole life since immigrating, and I always found it challenging to build a community here. As I was doing this film, one of my personal life goals was to make community and focus on that. So I was going super hard, trying to get into all the festivals I could and meeting people.

This was my first time doing the festival circuit, and I luckily had the support of folks at Creator Plus, and all of our producers and everyone. Our producer, Selena, actually had a film or two at CAAM previously. She was the one who connected the dots. I had always heard of CAAM in social media and the film network of my friends, but this was the first time I realized, “Oh wait, I can submit to CAAMFest.” Obviously, CAAM has such a good reputation and CAAMFest is one of the coveted festivals, for all of my Asian American friends especially, who I can now say that I’m so lucky to be in community with.

I had to go if we got in, and when we did, I met a bunch of people there and had such a great time with the Q&A. As the festival circuit continued, I kept engaging with people I had met at the festival, or films that I had seen there.

CAAM always stayed in touch and was the one that actually reached out to us about the PBS Short Film Festival. To be honest, I was really burnt out after the Oscar campaign. I put everything I had into this film, and now I just want to rest and start the next project because it takes a lot of energy to start the process again.

But then Czarina [Garcia] and the team at CAAM was so supportive. They championed the film so hard, and it was for the community, that I realized I had to do this. They guided me through every step and were so helpful. Even this interview: it’s so incredible how you champion filmmakers. It’s an actual community. That’s exactly what I was looking for when I started this whole thing a couple of years ago

Jonathan: Is there anything that hasn’t been asked in your interviews that you’ve been itching to share or thoughts that have been in your back pocket?

Mahnoor: Hmmm, I do feel people actually ask similar things, so there’s a lot that I don’t talk about. But I think something that’s probably not talked about overall in general is just how hard and stressful it is. How much of a handle you have to have on your mental health, to be able to go through the highs and lows of filmmaking, the emotional and personal life challenges that come with it.

I don’t know, that’s depressing, so I don’t know if you want me to talk about that [laughs]. I know filmmakers talk about that.

Jonathan: No, I appreciate you being real. At CAAMFest this year, I heard from a lot of people, especially in independent media, that have day jobs and struggle to find the balance and space for creativity and to push their projects forward and find funding, and do everything. I’m not a filmmaker, but it sounds very challenging, and all the more inspirational that there are folks like you that continue to do it.

Mahnoor: Especially these days, I feel you need a healthy amount of delusion to be able to make it as a filmmaker, and to keep believing in yourself because it’s just hard to believe in yourself in general. There’s this strange tension these days reading about the “death of cinema in America” and at the same time, especially post 2020, everyone’s need for diverse voices and filmmakers.

As filmmakers, I think we’re at this transformational point in the industry, where the industry and the people at the top have to adjust to the changing times. Whether that’s making a new model that works with streaming or a model that supports diverse voices. I hope that this is a transformational time, and the end result will be positive, when hopefully the dust settles from the strikes and COVID. I think about this a lot: where we keep asking for diverse voices, and we keep telling diverse people to enter filmmaking. But for me as an immigrant, I didn’t know anyone. I didn’t have any resources. I had to figure out every aspect of this process. I almost don’t feel right telling young women, especially of color, to just go into filmmaking blind because it’s so challenging.

And you find a way. But it’s not for the weak, and it’s not a financially sustainable career at all. I knew that, or I would hear people say that…I don’t think you realize in youth how many bills you will have to be paying one day.

Jonathan: I know that you’re working on a feature and a short. Is there anything that you want to share about that?

Mahnoor: Yeah, so this is happening. I feel like I was such a Debbie Downer with that. However. I’ve been really lucky, and I feel very blessed. EID MUBARAK opened a lot of doors for me, and I worked hard to suck the juice out of the festival circuit and the film.

So things have been looking up and are looking great. Actually, I shouldn’t be complaining or anything, and I hope that didn’t come across as complaining. It’s just hard. But obviously, I think we all find a way somehow, and all my friends have 30 jobs and are still pursuing filmmaking somehow.

With that said, I’ve been working on this film called Brown Girl. I always wanted it to be my first feature. It’s a coming of age movie, and I hope it will be my humble contribution to the teen girl comedy drama canon. It’s an homage to the Y2K teen girl movies that I grew up on, and it’s based on my experience growing up in Palos Verdes, an extremely affluent suburb in SoCal similar to the OC.

When I came, while I had been privileged in Pakistan, we had lost everything when we came here. So it was a very, strange experience being around that wealth and being in a bubble where racial dynamics and other dynamics were at play in interesting ways.

It’s a story about a Pakistani American girl called Sara, who wants to be popular really badly, and she makes a wish to be a popular girl, and the wish goes awry: when she wakes up the next day, she’s white, and then she has to figure out if losing her identity is worth gaining the privilege that she can now have.

Jonathan: That’s amazing. And I don’t think you’re being a Debbie Downer. I feel people always see the shine right when when people make it, or when they put something out, and all the focus is on, “Yay! Congrats!”

While the struggle in some ways makes the outcome sweeter in a sense, I hope we can get away from having to have the struggle to make it sweet. It’s this contradiction of creating, especially in these spaces. All that to say, we really appreciate you, and all that you’re doing through it all and excited to see what you continue to put out. Thank you for sharing time and space with me, and with everyone at CAAM!