What better symbol of a Chinese mother’s love than a steaming bowl of homemade soup? Nine years ago, Sharon Wong was trying a magazine recipe for a Southeast Asian-inspired peanut soup in her San Mateo, California kitchen when her two-year-old son walked in the room and started gagging. “I gave him soup to help him feel better,” says Wong. “He ate it and then threw up, and I saw that he was scratching his belly.” She didn’t realize at the time that even before his first sip of the soup, her son was having an anaphylactic reaction: the microscopic particles of peanut proteins released in the air during cooking were causing his throat to swell and close. Fortunately, she called her doctor, who urged her to take her son to an allergist right away.

Wong’s son, who is now 11 years old, is one of the 6 million American children affected by food allergies. Asian American children are 40% more likely to suffer from food allergies than the U.S population at large, according to a 2011 report published in the journal Pediatrics, the only American food allergy study which offers statistics specifically on Asian Americans. On top of that, treating food allergies can present very unique challenges within the Asian American community.

Occasionally, allergic reactions take place so swiftly that they are deadly. Eighteen-year-old BJ Hom of San Jose was the victim of such a reaction in 2008. The Hom family was vacationing in Mexico to celebrate both BJ’s birthday and his high school graduation. But after their first dinner at the resort, something went wrong. “Dad, my throat hurts,” BJ’s father, Brian Hom, recounts his son saying. “Can you get me some cough drops?” While the elder Hom went to the hotel gift shop to buy lozenges, BJ passed out in the lobby. By the time paramedics arrived the teen had died of anaphylactic shock.

The Homs knew BJ was allergic to peanuts, but nothing in their meal gave them any indication that traces of the protein might be present. Later conversations with the restaurant’s cook revealed that BJ’s dessert of chocolate mousse contained small amounts of peanuts. “I have a personal vendetta against food allergy,” says Brian Hom. In the seven years since his oldest son’s death, the San Jose father has made a mission of educating people about this commonly misunderstood condition.

Hom is especially worried that food allergies are not on the radar in communities of color. “It’s a stereotype that it’s a rich white family thing, that it doesn’t happen to Blacks, it doesn’t happen to Asians,” Hom explains. “It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or if you’re poor. The rich might just have more awareness.” Outreach to Asian Americans is important to Hom, who has appeared on Chinese language TV to talk about his son’s death.

Complicating the education efforts among Asian Americans is the lack of food allergy data specifically for minorities. “There’s so little done looking at these kids and how they show up with food allergies,” says Dr. Ruchi Gupta, MD Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern Medical and the lead researcher for the 2011 Pediatrics study. “Are they allergic to different kinds of foods?”

According to Gupta, Asian participants in the survey were 30% less likely to be diagnosed for their allergies. “Asian children may have food allergy, but their parents may feel that there’s not anything a doctor can do,” says Gupta, explaining that patients may just avoid an ingredient after a mild reaction, such as a rash or discomfort, instead of seeking medical testing to find out how severe the allergy is or if they are also allergic to other foods.

Why are so many Asian American kids developing food allergies when many of their parents and grandparents never heard of the concept? Studies in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology report that food allergies have doubled in the United States and the United Kingdom during the past two decades, but historical data from Asia is spottier. A 2013 study published in Asia Pacific Allergy reports that allergy rates in Asia during the most recent decade are increasing, albeit still lower than in Western nations. “It doesn’t seem to have any proclivity towards one ethnicity versus another or one child versus another,” says Kari Nadeau M.D. Ph.D., who is Director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy Research at Stanford University (formerly the Stanford Food Allergy Center).

A further breakdown of findings published in 2011 Pediatrics reveal that peanuts are the most common allergen among Asian Americans, as they are among the all American children, although peanut allergies are 30% more common among Asian kids. But Asian American kids are also frequently allergic to foods that are not considered common triggers in the United States. As a result, Asian American parents may need to be vigilant about accidental exposure to foods that are not generally thought of as allergens.

Jeannie Tsai of Mountain View, California has a four-year-old daughter who is allergic to multiple foods, including shellfish. Seafood stocks or dried shrimp may often be an ingredient in Asian meals, even though they are not visible in the finished dish or noted on the menu. “We went to a Japanese restaurant and my daughter developed hives around her lips after accidentally drinking some miso soup that was cooked with fish bones,” says Tsai. Shellfish allergy is much more common in Asian Americans than the general population. Breakout data from the 2011 Pediatrics study reveals that Asian Americans are almost twice as likely to be allergic to shellfish than other Americans, not surprising since the 2013 Asia Pacific Allergy report showed shellfish to be most common food allergen in many of the countries studied, including China, Taiwan and Thailand.

Most allergy sufferers, or their parents, have learned to be vigilant about avoiding exposure—checking labels, packing lunches, and avoiding restaurants. Brian Hom has been especially careful about food allergies since BJ’s death, but in 2013, Hom’s youngest son Steven was rushed to the emergency room after eating at a pho shop they’d frequented in the past without problems. “He ate the same thing for years, noodle soup with seafood,” explain Hom. “They changed the recipe, boiling it with peanuts.”

Food allergies seem especially cruel when people react to beloved traditional foods, causing them to avoid potlucks or family dinners for fear of unknown ingredients or cross-contamination. Cooking at home can even be a challenge. Wong has learned to prepare many Chinese foods that people typically eat at restaurants—such dan tot egg tarts or leaf-wrapped zhong common to dim sum carts—because of the danger that a steamer or pot of water may have also been used to cook foods that include peanuts. She reads labels and has even called distributors of packaged foods to inquire about ingredients, which is made difficult because of language barriers. “I speak Cantonese pretty well,” says Wong, a second-generation Chinese American. “But I don’t know how to read and write. I don’t have the words ‘anaphalaxis’ or ‘cross-contact’ in my vocabulary.”

Dr. Jae Rin Park, of West Point, New York, is a nutritional biochemist who is raising three young boys, each with multiple food allergies. Six-year-old Nathan is allergic to soy sauce, making it nearly impossible for his mother to prepare many traditional Korean dishes which she believes are important to maintaining optimal health. “I’ve tried to substitute coconut aminos and Bragg’s liquid aminos, both of which taste bad and nothing like soy sauce and also seem to elicit some kind of reaction in my son,” Park says. “I miss cooking certain dishes like bulgogi or kalbi.”

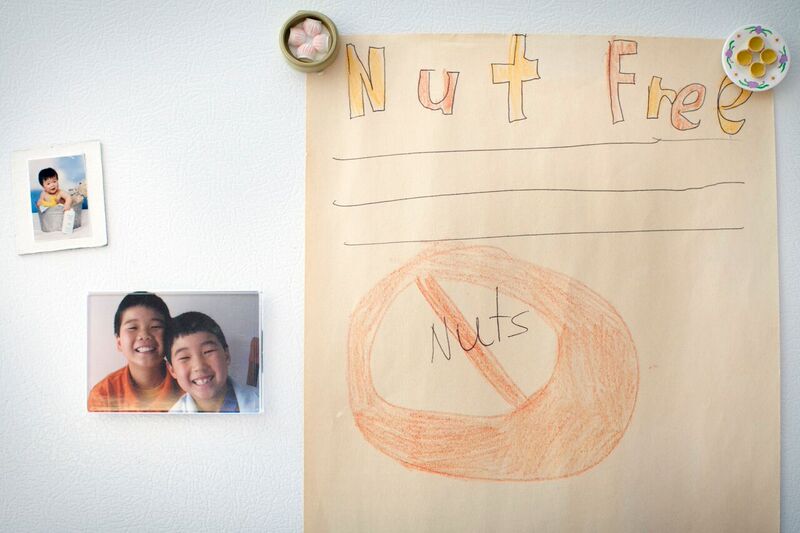

Dietary restrictions can even interfere with religious practices. Chicago resident Sharmila Rao Thakkar’s seven-year-old son is allergic to tree nuts and peanuts, preventing him from participating in the Hindu tradition of prasad, in which worshippers eat a bit of blessed food, usually fruit or the Indian sweet halwah, both which are often combined with nuts. “The priests pass it around and just expect all to take it, like communion,” says Thakkar. Since the prasad often contains allergens, Thakkar does not allow her son to partake, unless she or her mother have prepared it, and she is certain it is free of nuts.

Avoiding Foods is Not Enough

“Food allergy is different from lactose intolerance, which is very easy to treat, or celiac disease in which people cannot tolerate wheat,” explains Gupta. For example, The Centers for Disease Control reports that 90% of East Asians are lactose intolerant; their bodies don’t produce the enzymes to digest milk. The condition may cause discomfort, but can be easily managed by avoiding dairy products or by taking supplements. But for a person who is allergic to dairy, exposure to milk proteins triggers a potentially life-threatening response from the immune system. Stephanie Lau-Chen of Mountain View, California discovered her daughter’s severe allergy when the day care center called to report the one-year-old looked a little blue after taking a bottle. She rushed the toddler to the emergency room, where doctors gave her a shot of epinephrine, a drug that stops anaphylactic reaction.

Lau-Chen has had two other close calls with her daughter, who is now nine years old. “They’re always accidents,” Lau-Chen says, explaining that along with the incident at day care, her daughter has had two anaphylactic reactions under her own watch. “One time there was a Jamba Juice that we thought was fruit based. Another time was at a friends house and we were passing around drinks to the kids.” While Lau-Chen rushed her daughter to the emergency room after those incidents, she says in hindsight, she should have immediate used an epi-pen, a device that injects epinephrine into the bloodstream to stop the reaction.

“We’ve Been Eating This For Generations”

For many Asian American parents, one of the most formidable challenges is explaining the dietary restrictions to grandparents, who may be first-generation Americans or never heard of food allergies in their native countries. For immigrant families, in which generations may be separated by language and cultural differences, mealtime plays an especially important role. “There are some unique challenges for Asian American children with food allergies,” says Grace Peace Yu M.D. M.Sc., “Parents and grandparents sometimes show their love through food.”

In Dublin, California, Dr. Yu treats many East Asian and South Asian patients in her allergy and immunology practice. She has seen a dangerous trend of patients’ families attempting to ‘cure’ food allergies on their own. “What I’ve seen people do is bring their child back to India and bring them to Ayurvedic treatments,” says Yu. “Some of these treatments involve giving the child allergenic foods, and then have allergic reactions.” Because of the Asian high population in the Bay Area, her employer, the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, provides cultural awareness training for physicians.

Doctor’s children are not immune to food allergies, nor to the family tensions they can cause. Dr. Gupta’s research hit home when her own daughter was diagnosed as allergic to nuts, a common ingredient in her family’s Indian foods. “We’ve been eating this for generations and generations,” Gupta’s relatives told her. The co-author of The Food Allergy Experience, Gupta suggests defusing the tension by inviting skeptical grandparents to tag along on doctor’s visits. “Have the physician describe how serious it is to the family member,” advises Gupta. “Don’t put it on yourself. Put it on your doctor.”

If BJ’s Story Can Help Save a Life

Like Hom, Wong is also outspoken about food allergy safety, and notes that many of California’s leading food allergy advocates are also Asian American. In 2014, Wong testified before the California State Senate in favor of SB1266, a bill requiring epi-pens in all public schools. The California measure went even further than the federal law signed by President Obama in 2013, which gave school staff permission to administer epi-pens. While health care groups and allergy advocates backed the bill, teachers unions fought it on the grounds that educators might be forced into administering medication against their will. California lawmakers passed the bill in September 2014, joining five other states in mandating all public schools to carry epinephrine, which can be used on any child having an analphylactic reaction.

After Wong, a former school teacher, spoke in favor of the bill on a San Francisco TV station, an older relative became concerned about her future job prospects. “In Asian American culture, there’s a tendency to avoid causing trouble,” says Wong, “But I think when we keep quiet is when we put ourselves at risk.”

Could a cure for food allergies be near?

At Stanford University, Kari Nadeau M.D. Ph.D has spent over a decade researching a cure for food allergies. Nadeau’s group, the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy Research at Stanford University, currently has 13 different clinical trials designed to desensitize the immune system by administering microscopic amounts of allergens through a skin patch.

While the treatment may sound similar to Ayurvedic or Chinese medicine practices, Nadeau warns against attempts to treat food allergies outside of a medical environment. “The amount that you have to start with to get someone desensitized is miniscule and safety needs to be carefully watched by trained personnel.” Dr. Nadeau is optimistic about the treatment, although it may be years away from being available to the public. “At the end of the day, there is hope and promise for patients and families with food allergies,” says Nadeau. To date, over 200 people have had their food allergies successfully reversed through the Stanford program.

The trial group includes patients of various ethnicities and socio-economic levels, including Sharon Wong’s son, who is beginning to show signs desensitizing to peanuts. Brian Hom’s youngest son Steven also tested the patch for one year, but dropped out of the study due to potential interference from his asthma medication. Hom hopes his son can benefit from immunotherapy in the future, especially since the technology is on the fast track to FDA approval. In the meantime, he continues to advocate, speaking at food allergy conferences and organizing the annual Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) walk in San Jose. He hopes his story will show other Asian Americans that they are not immune to food allergies. “You know how death is in the Asian community, it’s sacred,” says Hom. “Losing a child is even worse. Take it seriously. Go get checked.”

—Grace Hwang Lynch

Grace Hwang Lynch is a San Francisco Bay Area freelance writer specializing in culture and parenting. Her writing has appeared in PBS Parents, Salon, BlogHer, and Library Journal. She also writes the award-winning blog HapaMama: Asian Fusion Family and Food.

This story is a part of Off the Menu: Asian America, a multimedia project between the Center for Asian American Media and KQED, featuring a one-hour PBS primetime special by award-winning filmmaker Grace Lee (American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs), original stories and web content.

This story is a part of Off the Menu: Asian America, a multimedia project between the Center for Asian American Media and KQED, featuring a one-hour PBS primetime special by award-winning filmmaker Grace Lee (American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs), original stories and web content.

MORE

Beef Yaki Udon (peanut-, tree nut-, egg-, dairy-, and shellfish-free recipe by Sharon Wong)

Participate in Indian American Food Allergy Survey

Dr. Ruchi Gupta is currently leading a pilot project to gather information about food allergies within the Indian American population. The survey aims to gather information about the most common allergens and symptoms within this community. Since the beginning of the year, over 70 participants have taken part in the survey. Gupta hopes the successful completion of this survey will lead to similar surveys within other demographic groups. If you are interested in participating in an online survey about food allergies, email Gupta at RUGupta@luriechildrens.org.

Pingback: URL()