|

LIFE UNDER CHINESE EXCLUSION

All Chinese immigrants entering the country were now scrutinized under the severe restrictions of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Port of San Francisco received the greatest number of Chinese. In the beginning, the Chinese were detained in a two-story, wooden warehouse operated by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (an overseas transportation firm). Located on the San Francisco waterfront, this makeshift detention "shed" was considered an over-crowded "fire trap." Reports of lax security, and improper ventilation and sanitation led to the construction of new detention facilities on Angel Island.

Though fraught with many of the same inadequacies, Angel Island Immigration Station eventually received tens of thousands of Chinese during the Exclusion period from 1910 to 1940. Entering Europeans, Japanese "picture brides" (destined to marry their prospective husbands by proxy in America), and other immigrants not subject to Chinese Exclusion were allowed to either land immediately in San Francisco, or experience short stays on Angel Island to confirm their status. On the other hand, U.S. immigration officials detained Chinese for extensive interrogations for several weeks, even months, and occasionally, a year or more.

The Chinese considered American Exclusion grossly unjust and discriminatory. Boycotts of American goods were organized in large Chinese communities as far away as the Philippines. Chinese diplomats in Hong Kong and community organizations in America would submit letters complaining about degrading practices and mistreatment by immigration officials. Many Chinese laborers and their family members resorted to methods for circumventing the Act. They would smuggle themselves across the border or purchase identity documents falsely claiming to be an individual of an exempt classification (e.g., a merchant or child of a merchant, or a U.S. citizen or child of a U.S. citizen). The creation of "border patrols," and indeed, the evolution of some of America's largest bureaucracies (the U.S. Customs Department, and Immigration and Naturalization Service, i.e., the I.N.S.) directly stems from much of the enforcement practices required by Chinese Exclusion.

Desperate attempts to enter America under Exclusion often involved the cooperation and assistance of different members of the Chinese community, as well as those in the white community. Chinese community organizations and import/export companies provided transportation, housing, exchange of important correspondence, and other means of support. Friendly members of the White community would sometimes bear both true and sometimes false "witness" to a person's residency or status as a merchant. Corrupt immigration officers could be involved in bribery schemes whereby false birth certificates would be issued or testimony documents changed. There were cases where such officials would be discovered and ousted from government service, only to find employment with some of the most prominent immigration attorneys in town.

Immigrants entering under false identities were often the able-bodied, male members of a family who were considered best suited to find employment in the United States. These male immigrants with false identity documents were commonly referred to as "paper sons." The Chinatowns of America have often been described as "Bachelor Societies," devoid of women and children. However, in reality, many Chinese men in America during the Exclusion era actually had wives and children residing in China.

Left behind in China, the wives of Chinese immigrants in the United States were referred to as "grass widows" or "living widows." Though they were married and assumed all the obligations of a wife, these women often led solitary lives separated from their husbands for years and even decades at a time. As a result, the normal formation of family life and community development both in the rural villages of China and the early Chinatowns of America suffered.

LEGACY OF CHINESE EXCLUSION

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a pivotal point in U.S. immigration history. Its impact most definitely reverberated throughout the Asian Pacific region as the United States subsequently restricted and/or excluded immigrants of Japanese, Korean, Filipino, and Asian Indian descent. By executive agreement, statute, and eventually, by a key clause in the National Origins Act of 1924 (which barred all "aliens ineligible to citizenship"), America closed its doors to more and more immigrants for reasons of race, ethnicity, and country of origin.

It was not until 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was motivated by China's war efforts against Japan in World War II, that the Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed. In statements made at that time, the repeal was in recognition of those fighting valiantly in China, and clearly an attempt to diminish propaganda efforts on the part of Japan that painted America as racist.

However, as a result of strict quotas instituted under the National Origins Act of 1924, immigration was still severely restricted for the Chinese. Though primarily passed to limit immigration from eastern and southern Europe, and Russia, immigration quotas were now tied to a very small percentage based on U.S. Census figures of how many people from a certain country were living in the United States in 1890. This translated to only 105 Chinese a year being permitted to enter the United States. A later amendment to the law defined this restriction further by applying to those who were by blood 50% or more Chinese from anywhere in the world (versus just one country).

Later provisions permitted alien Chinese wives and minor children of domiciled alien merchants to enter outside of these harsh quotas. There was also the War Brides Act, which permitted Chinese (among others) serving in the U.S. armed forces to bring their wives. However, the real key to reversing immigration restrictions and allowing for meaningful family reunification did not occur until the Kennedy and Johnson administrations finally abolished ethnic quotas with the 1965 Immigration Act. A painful and epic period in U.S. history finally came to an end.

Previous Page | Back To Top

SOURCE: Museum of Chinese in the Americas.

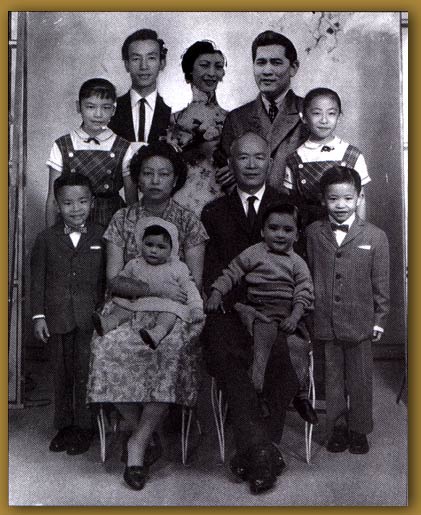

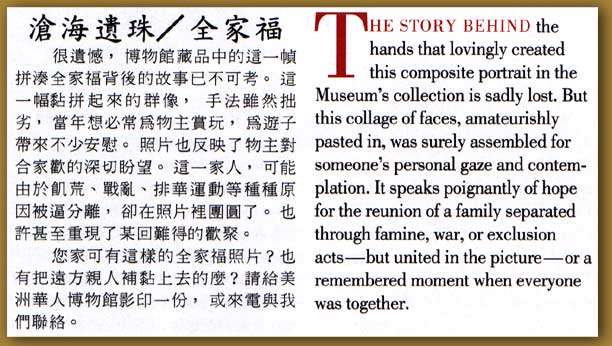

"Abandoned Treasures: Family Portrait." Bu Gao Ban

(Winter 1996): 8.

With permission of Mildred Y. Lee.

|