Nisei Cartoonist Jack Matsuoka’s Post-WWII Home Movies

CAAM is happy to present this selection of home movies from the family of the late Jack Shigeru Matsuoka (11/6/1925 – 8/26/2013), who served as an interpreter in the Counter Intelligence Corps of the Military Intelligence Service in post–World War II Japan. Matsuoka was born on November 6, 1925, and grew up in the farming town of Watsonville, CA.

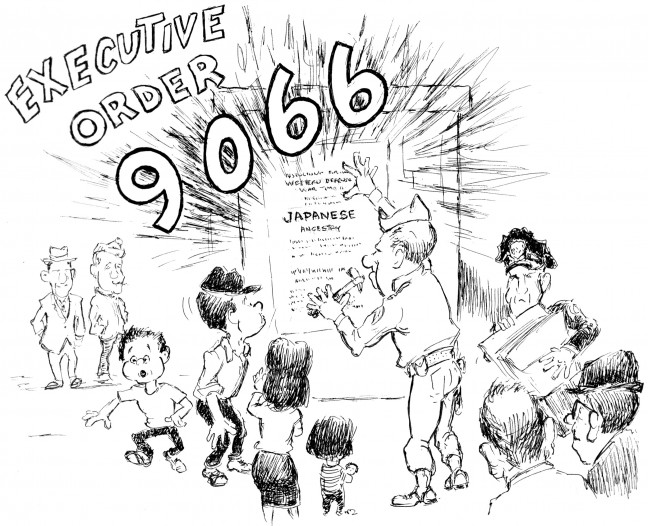

Jack Matsuoka was a teenager when his family was swept up in the WWII fervor. More than 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent to temporary centers and then internment, or concentration, camps during the war.

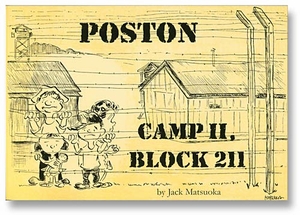

While in Poston, Arizona’s camp, Matsuoka observed the daily rituals. With no formal art training, Matsuoka drew for the camp’s newspaper, according to Densho. Matsuoka is best known for a book entitled Camp II, Block 211, (1974) which was later released as Poston Camp II, Block 211 (2003) with updated drawings and an afterward by the late Senator Daniel Inouye. The book is full of cartoon drawings from Matsuoka. A mostly self-taught artist, Matsuoka came out of the war and started working as a janitor at Cleveland School of Fine Arts, according to his daughter, Emi Young. The art school saw that he had talent and offered him a scholarship to attend. “He went to the dean’s office and they asked him to sketch something, and they said, ‘Okay, you’re accepted into the college. You’re on scholarship.'” But soon after, he was drafted into the U.S. military and went to Monterey to study for Japanese, in preparation to be an interpreter for the U.S.-led occupied forced in postwar Japan.

While in Poston, Arizona’s camp, Matsuoka observed the daily rituals. With no formal art training, Matsuoka drew for the camp’s newspaper, according to Densho. Matsuoka is best known for a book entitled Camp II, Block 211, (1974) which was later released as Poston Camp II, Block 211 (2003) with updated drawings and an afterward by the late Senator Daniel Inouye. The book is full of cartoon drawings from Matsuoka. A mostly self-taught artist, Matsuoka came out of the war and started working as a janitor at Cleveland School of Fine Arts, according to his daughter, Emi Young. The art school saw that he had talent and offered him a scholarship to attend. “He went to the dean’s office and they asked him to sketch something, and they said, ‘Okay, you’re accepted into the college. You’re on scholarship.'” But soon after, he was drafted into the U.S. military and went to Monterey to study for Japanese, in preparation to be an interpreter for the U.S.-led occupied forced in postwar Japan.

CAAM recently acquired the home movies of Matsuoka as part of our Memories to Light: Asian American Home Movies initiative. Most of the footage is from the time he spent in Japan after WWII, likely beginning around 1945. Matsuoka served as an interpreter and was a member of the Army’s Military Intelligence Service in occupied Japan between 1945-1961, according to Densho. He also later attended college in Japan, at Keio and Sophia universities, studying Japanese history, according to his daughter. “Matsuoka struggled through these schools on the GI Bill and became one of the few who experienced postwar life in Japan both as a member of the occupation forces and as a student,” according to the Rafu Shimpo.

Six of 7 reels were digitized by the Stanford University Libraries and shared with CAAM (one reel was too damaged to allow for digitization). The bulk of the footage takes place in Japan, with some footage of his family in Watsonville, a camping trip, and a visit to Monterey. The footage also included many sports scenes, from baseball to golfing to skiing, as he was a sports and outdoor enthusiast, according to Young.

The home movies show a little-known side of history. “Jack Matsuoka’s films offer a revealing look at occupied Japan through the eyes of a Nisei soldier

serving in the Military Intelligence Service,” said Benjamin Lee Stone, Curator for American and British History at Stanford University Libraries, which digitized Matsuoka’s home movies.

Japanese American linguists held a complex space in Japan after the war, according to some.

“In the wake of the devastating wartime internment, the Allied occupation of Japan was a godsend to Japanese Americans. It provided many Nisei [second generation Japanese Americans]—mostly in their twenties—with lucrative employment opportunities as interpreters and translators…In the continental United States, Nisei needed to rebuild their lives from scratch,” according to Eiichiro Azuma, who wrote “Brokering Race, Culture, and Citizenship: Japanese Americans in Occupied Japan and Postwar National Inclusion” for The Journal of American-East Asian Relations (Fall 2009).

The interpreters and translators—totaling up to 6,000 by the end of the occupation in 1952 who were mostly Nisei. They worked among mostly white American military officers in a relatively privileged position, a racial situation that “never existed for this persecuted minority in their home country,” according to Azuma. “…Their involvement in U.S.-Japan relations provided Nisei linguists with a fresh start as valuable members of the American national community….”

While in Japan, Matsuoka continued to draw. In 1956, he published Rice Paddy Daddy: The Adventures of G.I. ‘Bill’ in Japan. After returning to the U.S., Matsuoka worked at an import-export business. He transferred his love of sports, which is seen in much of the home movies, to a career as a cartoonist, including drawing sports cartoons. He drew the SF Giants, 49ers and Kristi Yamaguchi as she won Olympic gold. He also drew for The Pacifica Tribune from the early ’70s until 2000, and also the San Francisco Examiner, San Mateo Times and San Jose Mercury News, and ran a longtime comic strip “Sensei” in the bilingual newspaper The Hokubei Mainichi in San Francisco, according to the Rafu Shimpo. Matsuoka was a member of the National Cartoonist Association.

Matsuoka passed away in August 2013 at age 87.

Jack Matsuoka never had a chance to talk about what his home movies meant to him, or his time spent as a military interpreter in Japan. However, Young remembers that her father looked back on the time spent in Japan in a positive light. “He spoke very fondly of this time in his life. He was probably very happy living there,” she said. But, there were times when it was difficult being an interpreters, according to Young: “He spoke only of how difficult it was to interpret when the American leaders were not very gracious and Dad smoothed the language out in Japanese.” Matsuoka also had relatives in Japan, and some of the footage is of him and his cousins.

“I didn’t realize how much he was into filming,” Young said. “They sat in storage forever.”

—Momo Chang

Below, Young narrates the footage.

Japanese Americans in Watsonville

Watsonville had a significant Japanese immigrant population and was a close-knit community. Matsuoka’s mother was a midwife who delivered babies of farmers in her home. His father owned a car and helped people get around, and also participated in live theatre, according to Jack Matsuoka’s daughter, Emi Young. Here, Jack Matsuoka plays golf and his mother prunes chrysanthemums.

New Year – Mochi Pounding

Making fresh mochi is a family and community event to celebrate the new year, January 1. Footage circa 1953.

Jack Matsuoka plays baseball in Japan. His uniform is labeled CIC, which stands for the Counterintelligence Corps.

“He was very proud of his pitching.”

Jack Matsuoka in the Military Intelligence Service in post-WWII Japan

Camping and Honeymoon

The second half of this video shows Jack with his new wife, Rueko Itabashi, and her whole family. It takes place in Yokohama, Japan in 1955.

Digitized footage courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries. Audio recorded and footage edited by Davin Agatep.