Elizabeth Ai has the kind of disarming ebullience that makes people feel at ease. She opened our interview at a boba shop in East LA by paying for my drink and sweet potato fries, waving my credit card away with the air of a true Vietnamese auntie. In a gingham cap, a denim chore jacket and a fanny pack slung across her shoulder, she seemed to look the part as a CAAM Fellow: creative, on-the-go, in a rush to tell an important story. In this season of her life, the story Elizabeth wants to tell comes in the form of an upcoming film called New Wave, a historical coming-of-age documentary about the Vietnamese refugee youth in 1980s Orange County and how they expressed themselves through new wave music.

The project is a personal one. In 2018, when Ai was feeling nostalgic during her pregnancy, she began listening to the tunes her aunts and uncles had bumped during family parties. To her surprise, her husband recognized none of it. “I was like ‘Are you kidding me?’ Elizabeth recalls, realizing that not everybody was familiar with the soundtrack of her childhood. “On one hand, I thought it was so cool because it was like our own special thing, but that kind of propelled me to dig deeper and find the pioneers of this music scene and just ask questions. Why? Why this music? Why this scene? Why did you identify with this? Why did kids dress a certain way; why did they look like goths and punks while singing things like ‘you’re my heart, you’re my soul?’” (Yes, those are real lyrics from Modern Talking’s disco pop track You’re My Heart, You’re My Soul).

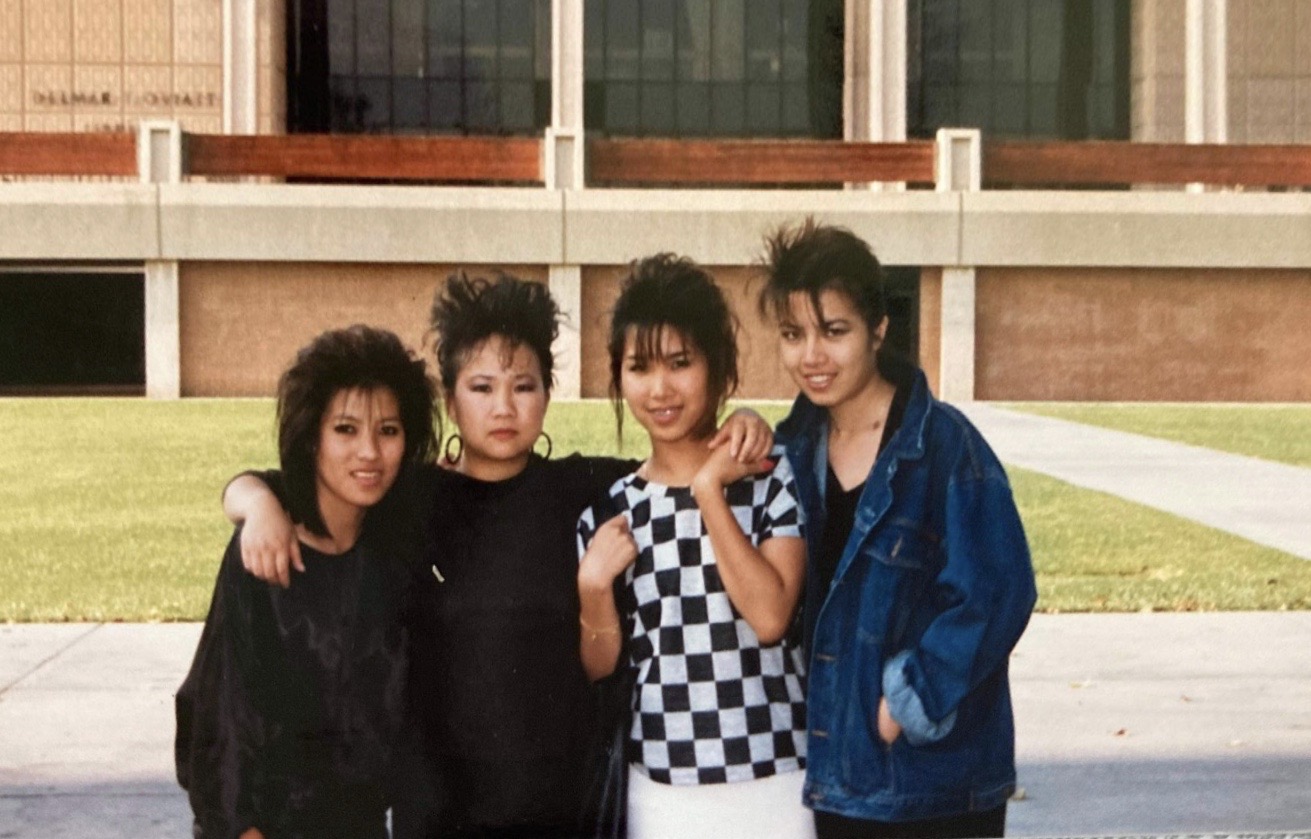

What Ai listened to as a child was, more specifically, electronic dance music with elements of pop, rock, and disco, otherwise known as Eurodisco and Italo-disco. The music became so popular that in this pre-Spotify, pre-Internet era, people smuggled cassette tapes back to the motherland before the trade embargo was lifted in the 1990s. On my drive to the interview, I listened to the @NewWaveDocumentary Spotify playlist she had compiled and the space-disco synth sounds instantly transported me back in time. I wasn’t the only one; When she posted a call on social media, asking people to share their memories and photos of the new wave 1980s, dozens of people messaged her on Instagram to send her old pictures of their family members, who were then the “goths and punks”, Vietnamese American teens with heavy eyeliner and aggressively teased hair. Ai had reached random corners of the Vietnamese American community with this specific, yet ubiquitous, cornerstone of our history and subculture.

When most American audiences think of new wave, they think of British groups—Depeche Mode, New Order or Pet Shop Boys. Ai is quick to point out that this doesn’t take away from the validity of how Vietnamese Americans identify new wave music from artists like Lynda Trang Dai or Trizzie Phuong Trinh. “I’ve been told so many times to change the title, that it’s not correct. And I’m like, ‘Well, what is new wave to you?’” recalls Ai, pushing back against the gatekeepers. “There was the British new wave, and then there was just this big umbrella term of new wave that just meant anything that was synthesized. So I’m like, I’m using that one, that’s how Vietnamese people identify it so I’m not changing my title. It’s like saying, ‘You can’t say you’re just American, you have to say you’re Vietnamese American.’ Like no, I’m just as American as you and new wave is just as new wave however anybody wants to identify it.”

Before Elizabeth Ai made her first feature length documentary, she had never planned on becoming a filmmaker. A few years out of college, the USC creative writing graduate and former student politician was working for a number of schools within the Los Angeles Unified School District, raising funds for art supplies and after-school art programs. She reached out to various artists to ask if they would donate work to contribute to these extracurriculars for under-resourced children, she was put in touch with David Choe, a Korean American artist and musician who eventually asked her for a favor in return. He was the subject of a documentary film directed by Harry Kim, and they wanted her to come on board as a producer. If she could coordinate fundraising events and shows for thousands of people, they pitched, producing wasn’t that much different. You just need a goal, a story you want to tell, and the ability to bring people together to make it happen.

So Elizabeth made her first film, Dirty Hands: The Art & Crimes of David Choe, an intimate perspective of the frenetic LA street artist’s life over the course of ten chaotic years. Ai’s career in film had begun, but the journey wasn’t without adversity. In 2008, right after the completion of Dirty Hands, the economy imploded in the aftermath of the subprime lending scandals. All the agencies who were at her door with opportunities suddenly weren’t returning her calls, and Ai wondered if her newfound career in film was over before it began. With some hesitation and a little shame, she began producing commercials. Now she speaks of it, if not fondly, then with pride and as an avid proponent of “keeping the lights on,” or doing what one must to survive while they pursue their craft. It contributed to her wide variety of filmography, boasting not only promotional content for Vice and National Geographic channels, but also several independent documentaries, fiction films, a dozen Emmy nominations and a 2012 News & Documentaries Emmy award. Her narrative work, nonfiction or fiction, always seems to champion an underdog of sorts. A Woman’s Work: The NFL’s Cheerleader Problem focuses on the cheerleaders filing lawsuits against their teams for wage theft and illegal employment. Saigon Electric, shines a light on underground street dancers in Vietnam. And of course, now there’s her latest documentary, New Wave.

As recently as one year ago, she was in a meeting regarding New Wave with a white male executive who told her, “I don’t know any Vietnamese people. Who’s gonna watch this movie?”

Elizabeth had an answer: “Lots of people. People who love music, people who love subcultures, people who love the underdog story. And of course there’s Asian American people, there are people who are interested in Asian American stories, and then there’s a whole globe of Asian people.”

Her answer, and her stance behind it, has been as much a work-in-progress as any of her creations. Imposter syndrome loomed over Ai for much of her career. As an AAPI woman and child of refugees with no connections, she was grateful to even be in such a competitive industry. Then she realized how much of her own identity she had suppressed in the process. “You start to believe the narratives industry gatekeepers tell. Now I’m saying it, it feels so cathartic, finally after working for more than a decade. I’m giving myself permission.” Now Elizabeth is going full steam ahead, owning and telling her own underdog story.

It’s this ethos, the same one that warrants hurdling over the suit-and-tie-shaped obstacles in white-dominated Hollywood, by which she defines her heroes in the industry. Elizabeth isn’t short on heroes. There’s the late Stephane Gauger, close friend and collaborator on Saigon Electric, who supported Ai during the early years of her career. There are her adventure companions, the producers on the New Wave documentary, Anh Phan and Tracy Chitupatham. There are figures like Geeta Gandbhir, her first-ever career mentor by way of the CAAM Fellowship, whose bravery in publicly discussing racial injustice in the industry struck a chord with Elizabeth. CAAM itself made it onto her list too: “Being a part of this was a huge feather in my cap and they’re one of the first to validate this story.” Then, there are the heroes closer to home: the displaced Vietnamese refugees who pioneered their own new wave movement.

In August, Ai presented a short sample video of New Wave at the 2021 CAAM Ready, Set, Pitch! to a panel of four judges. Her goal of taking an expressly Vietnamese American point of view on a topic that is usually framed by whiteness impressed the judges, who selected her to receive $10,000 in funding. “I found Elizabeth to be an incredible mentee,” Geeta Gandbhir said when I reached out to her for comment. “She has a lot of goals and really knows what she wants. She’s a very deep thinker and is thoughtful when it comes to our process.”

One of the main figures of the Vietnamese new wave movement and Ai’s documentary is singer Lynda Trang Dai, known for her provocative stage costumes and widely considered the “Vietnamese Madonna.” One of her biggest hits, Supermarket Love Affair, comes with a gloriously campy music video chock full of wistful glances in an Asian mart. It was the first time I had ever heard of anyone describing Lynda as a hero, but Ai clarifies: the heroes are not so much the individual artists as they are the group of people who refused to be defined by their collective trauma, and so chose to define themselves by something else. The ones who created a safe space before the term “safe space” was a thing. When discussing this, she gets emotional. “These singers, they busted their asses to prove that they exist, and not for the validation of white Americans,” she said. “They got here with their shirts on their backs and got on stage wearing their sequins, telling their story. They were just like ‘I just want to sing, and I want to do this for my people’. It was a lightbulb moment for me to realize that my heroes have always been there, right in my community.”

Ai is admittedly working on finding ways to refill her cup when she isn’t working. She’s protective of her weekends, which are reserved for family time, and chats with her sister, who lives in New York City but is close in spirit, on the phone. It’s difficult to balance being a director, a producer and a mom, but perhaps it stays tenable because the work itself is regenerative for Ai.

My last question for Elizabeth was the same one she had for the new wave artists who sang their way through her childhood: why? Why this story and why now, with such urgency?

The answer goes back to joy. Elizabeth wanted to feature her own community through a rare perspective of joy and celebration. “You can be healing from trauma, you can lose your homeland, you can experience great tragedy. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing else going on in your life. That doesn’t mean we weren’t these people with full lives and stories that span across a vast spectrum.” she says. The subjects of her film demonstrate the same, even without words, in their sequins on stage. I imagine they were tired, as is Elizabeth, as am I, of being a part of a community continually and solely defined by a war.

“As filmmakers from immigrant BIPOC communities, we find that we’re automatically otherized,” Gandbhir said. “She talked about being in the room with people constantly asking ‘Are you going to talk about the war? Is it going to be in there?’ When honestly, that’s not the focus of the story. We were very clear that while we want a broad audience to get it, she has to stay true to the community in the making of the film.”

As for the timing of it, Elizabeth credits another recent creation: her daughter and the legacy she wants to leave behind for her. Elizabeth had worked on plenty of Asian-centered stories, but never one that focused on Vietnamese Americans. “I feel like it was really important that I did this, especially for my daughter. When she grows up, I want her to know that filmmaking wasn’t just a profession, it was my contribution to something greater than me that I cared deeply about. If storytelling is the medium in which I communicate my passion, of course I’m going to share a story about our people.”

Ai hopes to wrap up New Wave by early 2023. Recently, she was announced as a Firelight 2021-2023 Documentary Lab Fellow to continue her work on New Wave. However, the 1980s Vietnamese new wave movement is rife with inspiration for Ai, who is working on a fictional series taking place in that world. When asked what core message she’s trying to relay with these works, Ai is silent for a moment. She distills her expansive project into three words: “everyone deserves love.” Everyone deserves love, even the misfits, even the unsung heroes from our childhood, even the people who aren’t often given a spotlight by white Hollywood. Now Elizabeth Ai is here, and she’s bringing her own spotlight.

Vivien Bui is a writer and content marketing strategist based in San Francisco. She is currently working on a speculative fiction novel.

2 Comments