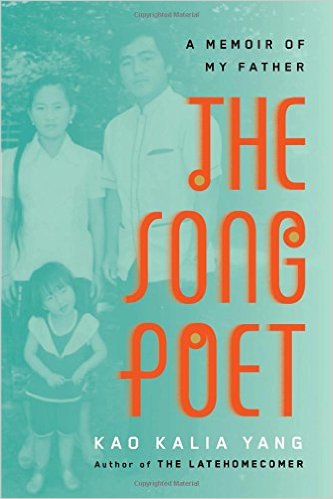

Kao Kalia Yang’s The Song Poet: A Memoir of My Father (Metropolitan Books, 2016) is necessary reading in this time of potentially abusive power and vulnerability. Yang takes on the voice of her father, Bee, narrating his life in Laos during wartime, and then as a refugee and immigrant to Minnesota. War was bad enough. Almost 1/3 of the Hmong population died during the Vietnam War. More bombs were dropped on Laos than on any other country in history. Once in the U.S., the forces of racism, school bullying, and workplace harassment and health hazards take their toll on the family. Bee Yang qualifies as a working-class hero, representative of so many with little means but ample heart and determination. Kao Kalia Yang’s work is in her family’s tradition of shamans and song poets, traveling through darkness but emerging with light. We are all vulnerable, some more so. Yang reminds us that this, and love, make us human. I interviewed Yang by phone. The following is an edited transcript. [Editor’s Note: Yang has contributed to CAAM’s website as a writer. Her essay can be read here: “Hmong New Year When Grandma Was Alive.”)

-Ravi Chandra

I really enjoyed your book. Many passages were very moving to me, and I think it’s an important read. Much of my work and interest lies in working with people with trauma. And being a victim of trauma, interpersonal and also societal trauma, makes one feel powerless and invisible. And your father’s song, poetry, and your writing give voice, power, and visibility, which are so necessary for healing, so thank you for writing this book.

Thank you so much, Ravi.

And maybe you could introduce yourself to people who aren’t familiar with your work.

And maybe you could introduce yourself to people who aren’t familiar with your work.

My name is Kao Kalia Yang. I’m a Hmong American writer working from the Twin Cities. The Song Poet is my second book. My first book, The Latehomecomer, came out in 2008. It was very much a love letter to my grandma and a story of the Hmong people and our place in America, how we got here, what we’re doing here. With the second book, I wanted to explore my father’s story. I asked him randomly one summer, I said, “Dad, how did you become a song poet?” He just looked at me and he said, “When I was very young, there were very few people to say beautiful things to me. I used to go from the house of one neighbor to the next, collecting the things people had to say to each other. One day, the words escaped as a sigh and the song was born.”

That’s what he said to me, and I thought, “Isn’t that beautiful. Wouldn’t it make a beautiful book?” So I suggested the idea. My father said, “Nobody wanted to read a book about men like him when there are men like Barack Obama in the world who can write for themselves.” But I started thinking that most of the world is made up of men like my father. And his life, too, has lessons to teach. And so, I’m a stubborn kid. My dad says I’m like a dog. If I smell the scent of a bone, I will follow and I will not stop. And so, I set out to do this thing, and it is done.

Maybe you could tell us more about the song poetry form, which I think of as linked to the oldest forms of storytelling.

Yes, Kwv txhiaj is rhymed poetry. I compare it to jazz because there is so much improvisation. I compare it to rap because everything rhymes and there’s a certain beat and a certain rhythm. Unlike rap or jazz, the human voice is your only tool, it is your instrument, and my father has been gifted with a wonderful instrument. And so, he sings beautifully. He’s known in our community not only for the beauty of his poetry but also his voice. And so, unfortunately, you’re not born necessarily with a good voice, and none of his children have inherited my father’s voice. But it is an old, old form as long as the Hmong people go back. It is, I am sad to say, a form that is hard for those of us who’ve been raised so far away from an idea of a home country or home a community to grasp and to master. And so, my father is, it’s sad to say, but perhaps he’s one of the last ones to really master the form in the way he has.

Well, I think you certainly do your part in translating that form to literature, and your book is actually written in chapters which you call tracks and album notes at the end. So maybe you can talk a little about how you conceived of that and how the song poetry form translated into your own writing.

In 1992, I was just a kid, and my father came up with an album of Hmong song poetry. It was considered a hit in the community. He made $5,000 profit. The goal was always that my father would make a second album. But that fall, my sister, Dawb, and I, said we needed new boots and wanted new backpacks, but we were embarrassed because our pencils were getting so short. And so, my father went to that $5,000 and he bought us the things that we needed and we wanted for the school year. When my younger siblings came along, they needed new things, too. And so, the $5,000 translated into bowls of rice on our table and chicken drumsticks in our hands, the clothing on our back. The second album never came out.

After my first book came out, a PBS producer came to our house to do a short special on me, and she asked my father, “How does it feel to give birth to a writer when you’re one yourself?” My father looked at her, he said, “I can barely write my own name. My daughter writes in English the stories I only wish I could paint.” And so, his words broke something inside of me. So my father has always said that when all is said and done, he wants it known that Bee Yang gave birth to seven children and that they became good people for America, good people for the world.

I wanted to tell him and tell the world that he was an artist and that he’d given the world so much more than just the seven of us. And so, I thought I would create the second album. That was my inspiration for the book. I wanted to record, in the form that I know best, the sounds of my father’s life, those that he sung in that song because of us.

And so, The Song Poet idea was born. It wasn’t born in chapters. It was born in tracks. You know, and as a writer I want…it was important to me, because my first book had been such a clear narrative in some sense. I wanted to shift my focus, so I took on his perspective, his voice, his song. That was the writing challenge before me. And then also the idea of an album is different than that of a cohesive narrative. And so, then I’ll need to play with the themes and the stories of his life, the songs of his life, in a different way. And so, that was my own effort to grow. And also, of course, to pay tribute to his form, Kwv txhiaj, to take on my most poetic voice, you know, my own position, to take on his poetry and somehow weave it together in the story of his life. So in the writing of that, I listened a lot to my father’s first album. Some of the tracks begin with little snippets from his songs transliterated, because I couldn’t do a clear translation, as best as I could. I don’t think it does justice to the depth of my father’s poetry, but it is the best that I can do. And so, that’s what The Song Poet…those are the organizing thoughts and the story of how I came to do it.

Well, your work is certainly very soulful and so touching. And one thing I remember you saying that you had a realization that your father’s songs were not only about hurt, but also about a boundless hope. And where does that boundless hope come from, do you think?

You know, my dad says that, “We are as far into the future as we’re ever going to get.” When I was a little kid in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, the 400 acres where I was born, the Hmong people only got food three days out of the week. My father used to take me to the top of the trees, hold me up high, and tell me that one day my feet were going to walk on the horizons my father’s never seen. So the place where people bartered for little girls like me with bottles of fish sauce, my father always said I was a captain to a more beautiful future.

I think that so much of the push in his life has been for my siblings and I. You know, he says that at his best he is always the father he imagined for himself. My grandpa died when my father was just two years old. And so, my father has become the father that he wished for himself. One of the things that happened to him, his father died and left him, so he never wanted to leave us. And in many ways, I think that’s been one of the biggest reasons why my father stands in a world where it would be easier at times to lie down, where the exhaustion of the human body grows so heavy that the human heart cannot get up.

My father has struggled for us. He wants us to see what it’s like to stand up. He reminds me all the time that all of the people in the books, you know, the great ones, Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, all the people we study, that they’re in those books not because they succeeded. It is because they tried and failed and tried again, and in the end, they built a change that was bigger than themselves until others have served in the place. And that is how life happens.

To most of the world, my father is a machinist without much by way of words. But to me, he is the song poet in my heart, my biggest literary influence. You know, forever when people would say, “Who are the writers you respect?” I would think immediately of the writers I’d studied. It wasn’t until after The Latehomecomer was published that I would feel like my father was my first teacher in how words could work, not on behalf of the human life, but on behalf of the human heart. And so, I don’t know, I want to say it’s his children. I think he would say immediately that it was his children, and, of course, this love for my mother, the sustaining love, that is stronger than my father, I think. My mom’s love is stronger than he is at times. That’s how you’ve made it through. That’s how he makes it through.

I certainly could see from your book and from what you’ve told me that your family stuck together, shoulder to shoulder, in the midst of suffering. And the love between you is palpable against a backdrop of a world that can range from cruel to indifferent at times. And I think that’s what’s so important. I mean, I think certainly now the problems of being powerless or being caught up in forces that are more powerful than you … I think we can’t really be in denial, if we ever were, about that. And so, your book really brings this story, your story, to consciousness at an important time.

There were so many scenes of your family trying to care for each other. With your brother, you called it “surviving the statistics and realities of growing up poor and different in America.” And there are all these stories of vulnerability and the response to vulnerability, scenes of your family trying to care for each other, your sister winning the local spelling bee and using the $50 prize to buy new shoes for your father. Your brother, his struggles with being bullied in school, and your family’s difficulties in coping with that. Your father’s troubles at the plant, breathing in metal carbide particles. Your sister writing a letter to advocate for him with plant management. And his difficulties dealing with illness and doctors.

I think that theme of showing vulnerability…I don’t think you outright blame anyone for the difficulties that have been encountered, but certainly, singing your story, writing our family’s stories of vulnerability are so important. Please tell us more about the feeling of vulnerability in your work and where you find your own sense of hope and coping with vulnerability.

I’m so impressed with how closely you read the book, all of the scenes you can bring up. It’s very rare an interviewer has read such carefully, actually. So thank you for that. That’s a big, I think, affirming thing you can give a young writer like me, when a smart person reads very carefully and takes your work seriously. So thank you for that.

You’re welcome.

So I’m married to a white guy, and, you know, I cut my mom and dad’s toenails because it’s hard for them to bend down because they both have carpal tunnel. And so, their fingers are stiff and it hurts. Because they’re always standing on their heels, the muscles inside are all soft, and so I massage their feet. Things like this. I cannot imagine my husband Aaron doing it. He cannot imagine himself doing it. His parents cannot imagine him touching them in these ways. But for me and for my siblings and for some of the other kids I grew up with and the kids I know, my cousins, it’s the way you make possible tomorrow for everybody to stand together. I think in a house like ours…there’s so many houses like ours throughout this whole country and this whole world, there is no room to hide. And so, you share and you help each other as you know how.

In a house without much money, you know, I remember when it was Mom and Dad’s birthday and we wanted to do something special, we would clean up the house for them and surprise them after work. My older sister used to do that for Mom and Dad, and that was our way of gifting them. When the kids got bigger and they started asking questions about Christmas, we re-wrapped our old toys and so gave them the opportunity to open them. These things, without money, without room, little space, you cannot hide from each other.

I think, in many ways, that’s why I’m so comfortable with vulnerability. I see it in so many people around me, and sometimes they have the language for it. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes the culture itself didn’t lend itself. People put on such a strong facade, I think, to the world, and that’s kind of sad to me. It’s misleading. Human connections happen when we understand each other’s vulnerabilities, not just strengths. And we live in a world that is continually trying to be strong in some places, in some ways, in some instances, as a method of hiding our vulnerabilities. And so, I think the strength of my writing is that I’m not scared to talk about what makes us reach, so we can continue one more day together, strong or not.

Your stories really reached me, and I think would reach a lot of people, because I think vulnerability and difficulty and going through trauma, I mean, these are parts of life, and we can’t escape them. We have to face them. Vulnerability is what makes us rely on each other and wants to make us reliable for each other as well.

That’s because you can’t survive by yourself. My dad says we can all walk to the future by ourselves, but we can only progress if we walk together.

That’s right. I think in this culture, America being such a strong and powerful country that we get so many messages about being perfect, being invulnerable, being strong, not showing emotions, not showing anything that looks like “weakness.” But I think that has to shift if America is to really continue to develop and to be strong. We have to face the reality of our own human condition. And I think finding our common humanity is so important, and your book just highlights common humanity so well.

We’re in complete agreement here.

What else is in the works for you right now?

Right now, I’m seven chapters in a fictional narrative. I grew up reading “Little House on the Prairie”. One of the most moving books for me when I started reading more complicated works was “The Jungle”, because it resonated so closely with the life I saw my mom and dad living in the factories of Minnesota. And so, this new book, I thought, I’ll go back to the beginning. When I got my first library card, I ran to my grandma and I showed her. It was a purple Saint Paul public library card. My grandma said, “What’s that?” I said, “It’s a library card.” She said, “What’s a library?” My grandma’s never been to school. She never learned how to read or write. And I said, “Grandma, it’s where they hold all the stories of the world.” And she said, “Is there a story like mine?”

And I thought about her words for years. Last year, I had the opportunity to do a residency in one of the Saint Paul public libraries, seven weeks, and I thought I would do a residency in children’s literature because I was pregnant with identical twin boys at the time, and I thought I’m gonna have kids, you know, I had a one-year-old daughter, and so I should learn what’s out there. And I read through all of these books, and there were no stories like my grandma’s. And so, I started thinking about the instance in which…the reality in which I could look my grandma in the eye and say, “Yes, your stories are also on the bookshelves of a bigger world.” And so, I started writing Medicine Girl, which is inspired by my grandma’s life.

My grandma, she became a healer because her parents had died, her brother, the older siblings had died, leaving her the oldest. And so, she thought that if she could learn how to heal, she could fight death. And as my grandma would tell me, “You grow up and you grow old and you learn that there are sometimes things that happen in life that are worse than death.” And so, that’s the inspiration behind it. It’s a fictional narrative, but that’s what I’m staying with. And then I imagine it as one of two books. The second would be Rise of the Shaman, because my grandma was a shaman. Because I’m incredibly spiritual and sensitive to the forces around me and because I’ve always had this fear of the dark and other spaces, and I wanted an opportunity to give me, because I understand as a writer that if the work isn’t beneficial for you, then it stands no chance of being useful for your readers. So I wanted to give myself the opportunity to venture into those dark spaces. And so, Rise of the Shaman will be the second one. I’m on the first book. I’m seven chapters in.

Well, I look forward to reading those. I personally have been so transformed by the stories of refugees from war and trauma survivors. Actually, I started out in family medicine in Minneapolis.

You did?

Yeah. And a lot of my patients were Hmong and Vietnamese and Somali refugees, and their stories became more compelling to me than their physical illnesses, and often, their physical illnesses sprung out of their emotional suffering and their life suffering. And so, that’s why I switched into psychiatry. I think I always try to stay grounded in the reality that my patients experience, because whether we’re talking about politics, or economics, or sociology, or literature, it always comes down to human stories and trying to relate to each other. I think for people who don’t have the good fortune to work with people who’ve gone through these experiences, your work certainly brings the messages home. So thank you so much.

Thank you. You probably worked with members of my family. The Hmong community is incredibly connected.

You know, I might have. I delivered quite a few babies, including Hmong babies. So yes, had wonderful experiences… and was welcomed around the dinner table with my Hmong friends. So I have many good memories of Minneapolis. Thank you again for your wonderful writing!

Thank you!

+ + +

Ravi Chandra is a psychiatrist and writer in San Francisco. He writes the Pacific Heart blog for Psychology Today, where he published “Letter to Young Activists”, about self care in this time of social turmoil. His essay “Data, the Social Being, and the Social Network” was recently published in the Queens International catalogue. More MOSF posts can be found here and here. You can sign up for a newsletter to get word about his writings at www.RaviChandraMD.com.

Awesome!!!